Korea’s Top 500 Tourist Destinations: The 2025 Tourism Landscape through Traveler Sentiment Analysis

Soocheng Jang, Professor at Purdue University & Director at Yanolja Research / [email protected]

Kyuwan Choi, Professor at Kyung Hee University & Director at H&T Analytics Center / [email protected]

Prior to the pandemic, the Korean tourism industry demonstrated sustained quantitative growth, attracting 17.5 million inbound tourists in 2019. While the sector experienced a significant contraction due to the exogenous shock of COVID-19, the post-reopening recovery has been rapid, and it is now certain that inbound figures this year will surpass 2019 levels. Furthermore, with projections indicating that inbound arrivals could exceed 20 million by 2026, the industry is poised for continued growth in the mid-to-long term. This resilience attests to the fact that Korea’s tourism resources possess enduring appeal for both domestic and international travelers.

Concurrently, however, consumer behavior in travel has undergone a radical transformation driven by the digital environment. Travelers, who once relied on static information sources such as guidebooks, now leverage social media and online channels to select destinations and formulate itineraries. In essence, travelers are evolving into “active consumers” who search for information in real-time within digital ecosystems, curate personalized journeys, and actively disseminate their experiences.

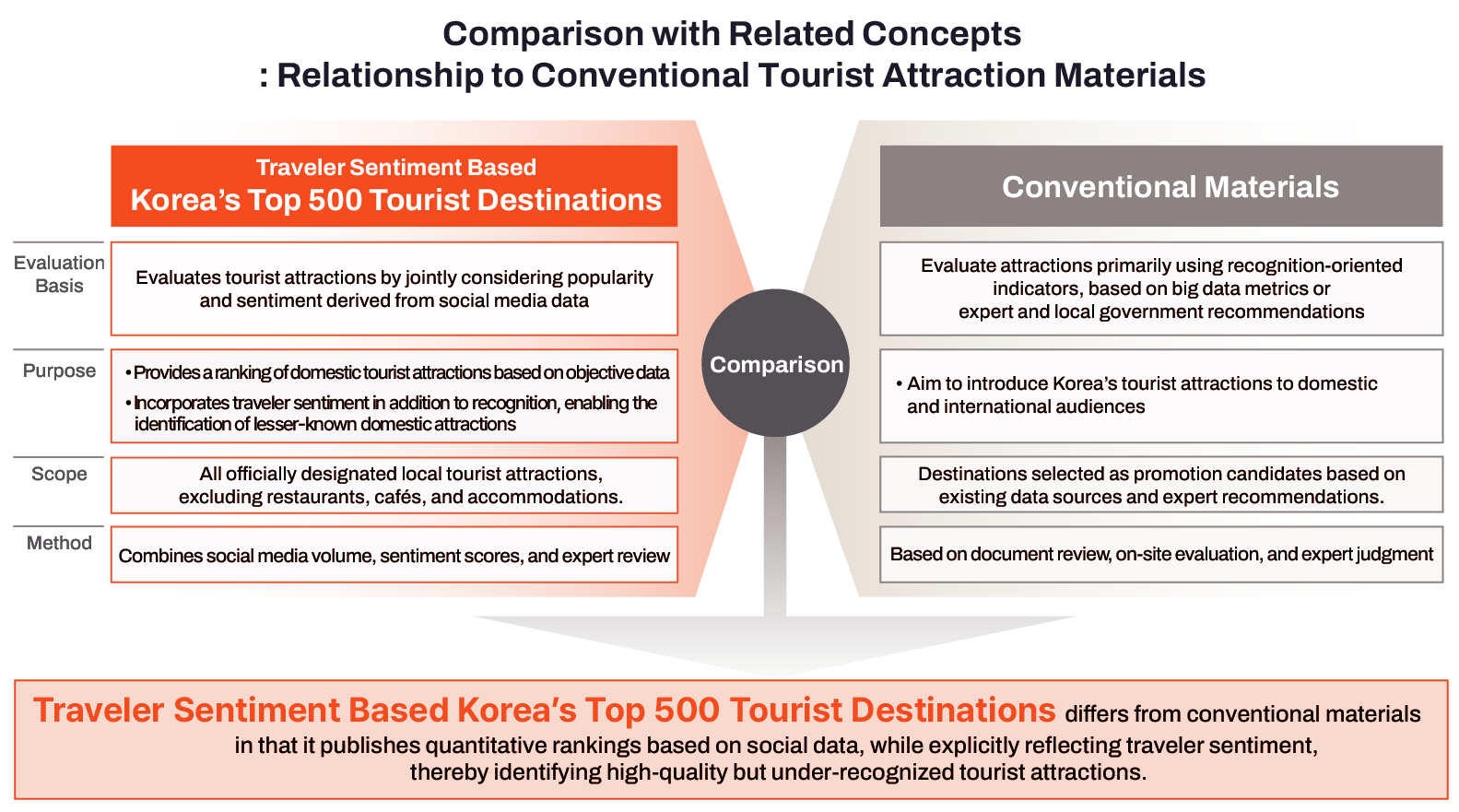

In light of this paradigm shift, existing destination rankings and recommendations, while still serving as reference points, exhibit inherent limitations. For instance, the “100 Must-Visit Tourist Spots in Korea,” selected biennially by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and the Korea Tourism Organization, as well as rankings on private portals, rely predominantly on expert assessments and historical visitor statistics. Such metrics risk inducing the “Matthew Effect,” where established destinations are repetitively selected, thereby creating structural barriers to the discovery of latent high-potential sites. Moreover, the reinforced perception that “high visitor volume equals a superior destination” exacerbates information asymmetry, leading to a concentration of demand in the metropolitan area or specific regions, irrespective of actual traveler satisfaction. Consequently, supply-side indicators or expert-centric selection methodologies are insufficient to fully capture the experiential value perceived by actual travelers.

Therefore, this study adopts “Traveler Sentiment Evaluation” as a core methodology, transcending the limitations of traditional quantitative approaches. By moving beyond uni-dimensional metrics such as simple visitor counts or search volumes and integrating the analysis of emotional language accumulated in social big data, we aim to re-illuminate the intrinsic value of tourist destinations. This approach allows for a more precise interpretation of evolving tourism trends and the discovery of hidden gems—regional sites with high potential that have yet to receive mainstream attention alongside established landmarks. Ultimately, this report is envisioned as a strategic milestone, guiding the Korean tourism industry beyond the phase of mere “quantitative expansion” toward a stage of “qualitative maturation.”

As aforementioned, the contemporary traveler is no longer a passive observer. They are active “organisms” who search for information in real-time on digital platforms, curate itineraries to suit their personal tastes, and disseminate their experiences back through networks. The traveler has transformed from a mere consumer of pre-packaged tourism products into an active agent who interprets, selects, and reproduces information.

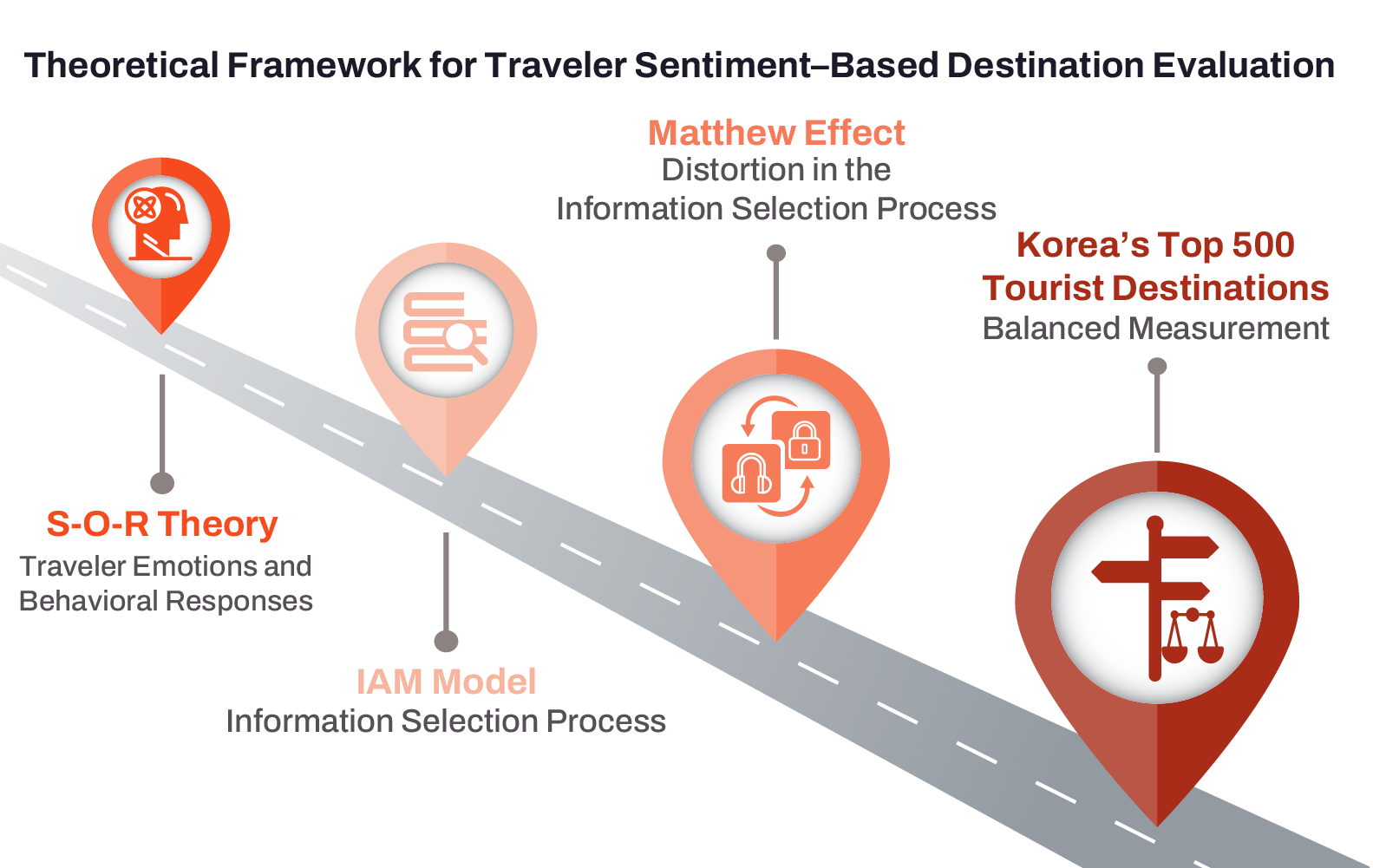

Reflecting this structural shift in traveler behavior, this study aims to measure the appeal of tourist destinations more scientifically. To this end, we have reinterpreted the classical environmental psychology theory of S-O-R (Stimulus–Organism–Response) and the Information Adoption Model (IAM) from the information systems field to fit the modern digital environment. Furthermore, we have applied an integrated analytical framework that accounts for the Matthew Effect occurring within platform environments.

S-O-R Theory in the Digital Travel Ecosystem: Stimulus, Affect, and Diffusion

The S-O-R (Stimulus–Organism–Response) paradigm, a representative theory in environmental psychology explaining human behavior, was proposed by Mehrabian & Russell (1974). This theory posits that external environmental stimuli affect an individual’s internal state (Organism), which in turn elicits behavioral responses of approach or avoidance. Applied to the tourism context, this framework allows for a systematic understanding of the entire process wherein a traveler encounters an external stimulus, is emotionally moved, and ultimately takes action to travel.

A critical point to note in the tourism environment of 2025 is that a significant portion of these stimuli no longer originates in physical spaces but in digital spaces. A short-form video of a red sunset in Jeju on Instagram, the vivid sounds of Busan’s Jagalchi Market in a YouTube vlog, or the ambiance of Gangneung’s Coffee Street described in a blog go beyond simple information delivery to directly stimulate the traveler’s senses and emotions. These function as “digital pheromones,” awakening the desires of potential travelers much like biological signals inducing specific behaviors.

However, not all stimuli exert the same effect. The traveler, as an organism, possesses distinct experiences, values, and learned judgment criteria. In this process, the modern consumer’s “psychological immune system” plays a crucial role. Past exposure to exaggerated advertisements, staged promotional content, and manipulated reviews has led consumers to form defensive attitudes toward commercial messages. Consequently, stimuli lacking authenticity are easily rejected, whereas testimonials from ordinary people with similar tastes or content from trusted influencers bypass this immune system to directly stimulate the traveler’s affect.

This internal change ultimately leads to a response (behavior). Tourism behavior in the digital age extends beyond the mere act of visiting; the delight or disappointment felt on-site is reprocessed into photos, videos, and text, and then diffused back into the network. Thus, tourism behavior is not a one-time consumption event but forms a diffusion structure where stimulus and response circulate repeatedly. This study seeks to analyze what compels travelers to open their hearts through this expanded S-O-R structure.

Reinterpretation of the IAM Model: Destination Selection and the Logic of ‘Queuing for Restaurants’

While the S-O-R theory explains the macroscopic flow of traveler emotion and behavioral diffusion, the Information Adoption Model (IAM) is a microscopic theory explaining which information travelers trust and adopt. According to Sussman & Siegal (2003), when individuals accept information, they use Argument Quality (the persuasiveness of the information content itself) and Source Credibility (the trustworthiness of the information provider) as key criteria.

Applied to the tourism context, a traveler’s behavioral response is not determined solely by the quantity or frequency of stimuli but depends on how credible and meaningful that information is. The most intuitive analogy for understanding this information adoption process is the phenomenon of “queuing for restaurants.”

A destination’s reputation is measured by the volume of mentions generated on social media and online platforms—namely, buzz volume. This is akin to a long line in front of a restaurant. Even without actual experience, travelers acquire social proof that a place is “likely verified” simply because many people are talking about and visiting it. In this sense, reputation serves to reduce uncertainty in initial selection.

However, a long line does not guarantee superior food quality. Similarly, high buzz volume for a tourist destination does not guarantee actual satisfaction. This is where a destination’s attractiveness becomes critical. Attractiveness refers to the quality of the emotion actually experienced by the traveler, which is measured in this study by the ratio of positive responses derived from social big data sentiment analysis.

As the IAM model suggests, while reputation determines initial inflow, attractiveness determines sustained diffusion behaviors such as revisits and recommendations.

The Matthew Effect and Algorithmic Bias

Another theoretical background that cannot be overlooked in the modern tourism ecosystem is the Matthew Effect. Derived from the biblical verse, “For to everyone who has will more be given, and he will have an abundance. But from the one who has not, even what he has will be taken away” (Matthew 25:29), this concept is highly apt for explaining algorithmic bias in digital platform environments.

Recommendation algorithms on digital platforms fundamentally operate in favor of subjects with abundant data. Already well-known tourist destinations, having high search volumes, reviews, and mentions, are exposed at the top of platforms, creating a virtuous cycle that induces even more visits and data. Conversely, small-scale regional destinations with insufficient initial data, despite possessing outstanding potential, fall into a vicious cycle where they disappear from public view without being selected by algorithms.

This aligns with the IAM structure described earlier. Source credibility is reinforced through data accumulation, but in platform environments, this credibility is automatically amplified by algorithms. As a result, a traveler’s choice is structurally limited by the “visible options” provided by the platform rather than individual judgment. In other words, the Matthew Effect is a systemic bias operating at a stage prior to traveler sentiment and information adoption.

Recognizing this algorithmic bias, this study attempted to include tourist destinations as broadly as possible through a near-census data survey, aiming to bring to light those obscured by existing recommendation systems. This is not a simple ranking calculation but an attempt to correct the destination perception structure distorted by the Matthew Effect and to re-illuminate “hidden gems” with genuine appeal based on data.

Synthesizing the theoretical background of this research: the S-O-R theory explains how traveler emotions and behaviors are formed and diffused; the IAM model explains which information is selected in that process; and the Matthew Effect demonstrates that this selection process is never neutral and can be distorted by platform structures. “Korea’s Top 500 Tourist Destinations” is an endeavor to comprehensively integrate these three theories to measure the true appeal of tourist destinations within the digital travel ecosystem in a more balanced manner.

Data Collection and Refinement

This study adopts a Digital Ethnographic approach, prioritizing the observation of what travelers actually perceive, feel, and articulate within the digital realm, rather than solely pursuing statistical precision. Travelers navigate online to search for information and share experiences; these digital footprints cumulatively construct a topography of collective perception and emotion. This study seeks to objectify the attractiveness of tourist destinations by collecting and refining these “digital footprints.”

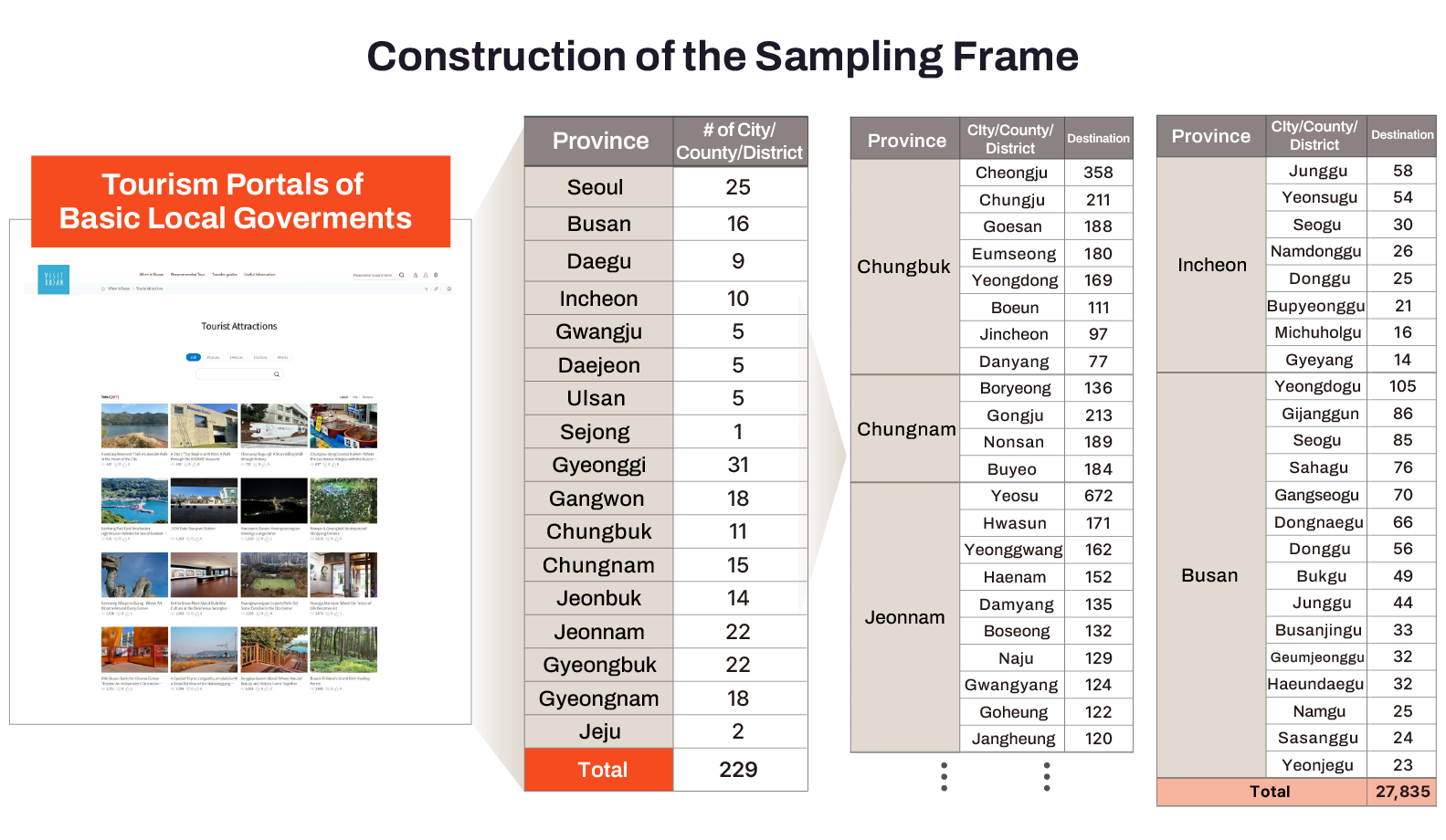

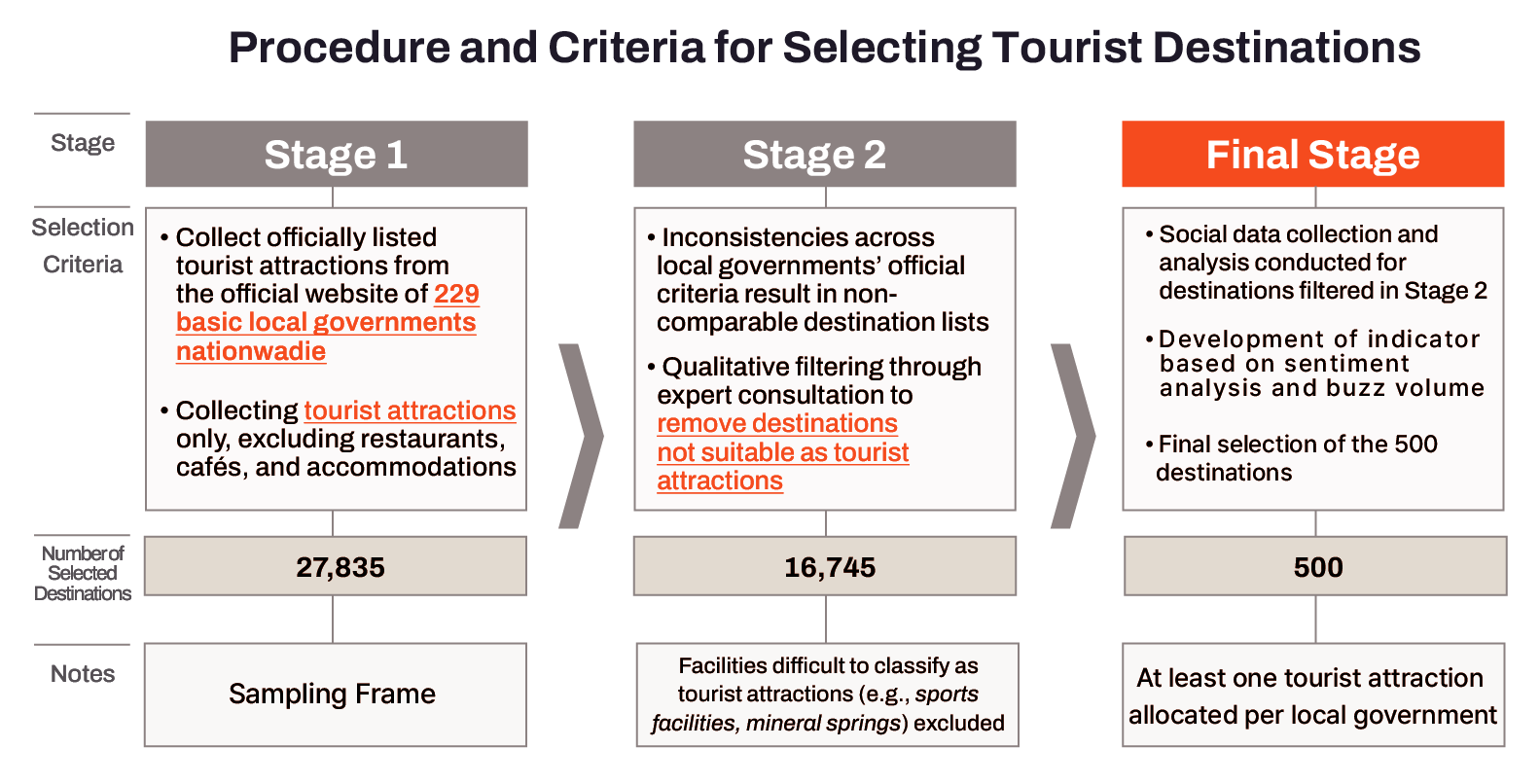

First, we maximized the expansion of the sampling frame. We conducted a near-census collection of tourism-related resources listed on the official websites and tourism portals of 229 basic local governments (Si, Gun, Gu) nationwide. Consequently, we established a sampling frame of 27,835 locations, a figure that approximates the total population of domestic tourist destinations. This research design aims to mitigate the bias inherent in recommendation-based evaluations of limited candidate pools, such as the existing “100 Must-Visit Tourist Spots in Korea,” and to discover hidden gems—smaller yet robust destinations—through a data-driven approach.

Second, strict filtering was performed. To ensure clear identity as a tourism destination, general restaurants/cafes, accommodation facilities, and community-centric sports facilities (neighborhood parks, mineral springs, etc.) were excluded through expert review. Through this process, 16,745 locations were finalized as the analysis targets. In other words, rather than creating a simple “tourist recommendation list,” we aimed to encompass the “tourism destination ecosystem” as broadly as possible while refining items that could blur the focus of the analysis, thereby enhancing data interpretability.

Third, data sources and channels were designed. We utilized the text database of VAIV Company, Korea's largest social big data analysis firm. We selected channels where travelers’ voluntary experiences are accumulated—such as Instagram, YouTube, blogs, and online communities—as primary sources, while excluding news channels with a high proportion of promotional articles to increase data purity. This is based on the judgment that “words left by those who have visited” reflect a destination’s actual attractiveness more accurately than advertising copy.

Fourth, the analysis period was set to the recent one year, from October 2024 to September 2025, to reflect both the latest trends and seasonal characteristics. This allowed us to capture the current sense of the travel market without being biased toward specific seasons or events.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Objective | Selection of 500 tourist destinations in Korea based on social big data |

| Sampling Frame | 27,835 locations across 229 basic local governments nationwide |

| Data Collection Method | Collection of all documents containing the destination name |

| Data Collection Channels | Data sources were selected by excluding news channels, which primarily contain promotional materials or event/issue-driven content not aligned with the study objectives - YouTube, Instagram, Blogs, Facebook, X, Online Communities(Café) |

| Analysis Period | Most recent one-year period: 2025 (October 2024 – September 2025; data aggregation period) |

| Data Collected and Analysis | Buzz volume and sentimeny analysis by destinations |

| Data Provider | VAIV Company |

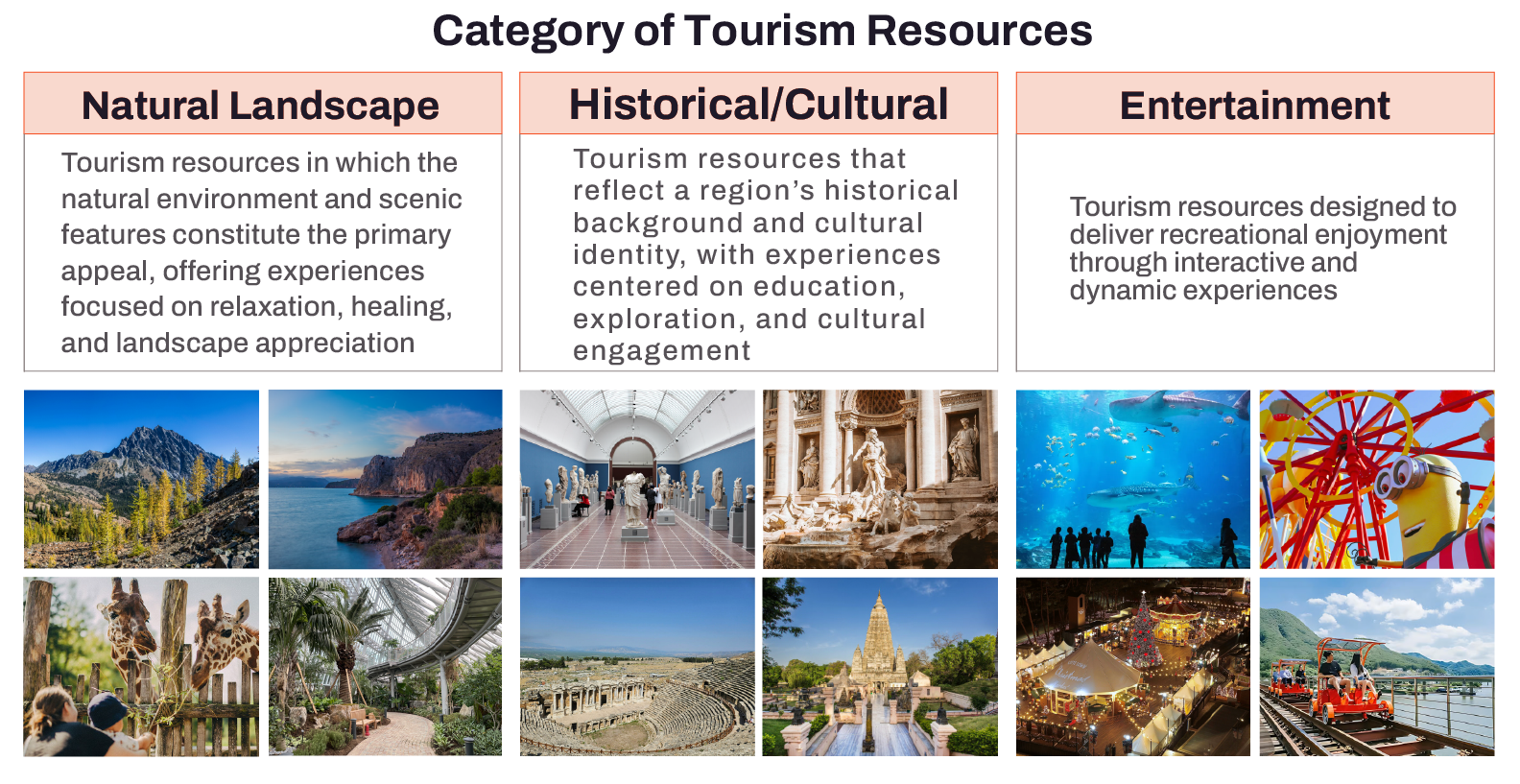

Fifth, to systematically compare and analyze the characteristics of tourism resources, the final targets for analysis were classified into three major categories based on their inherent nature. This classification is not intended to determine the “superiority” of destinations but serves as an analytical framework to more precisely interpret differences in the types of experiences travelers anticipate and their subsequent emotional responses. Specifically, tourism resources were categorized into three types: ▲ Natural Landscape, ▲ Historical/Cultural, and ▲ Entertainment.

Sentiment Analysis and Indicators

The essence of big data analytics lies in extracting meaningful insights from vast amounts of noise. This study sought to transcend the mere frequency counting of words, aiming instead to interpret the direction and intensity of emotions embedded within the context.

To achieve this, a Transformer Architecture-based Natural Language Processing (NLP) model was utilized. For instance, the phrase "It was so crowded I nearly died" expresses dissatisfaction regarding congestion, whereas "It was crowded so it felt like a festival" expresses vitality and enjoyment. Even if surface-level words are similar, the sentiment can be diametrically opposed depending on the context. This study distinguished these nuances and calculated positive/negative emotional responses by incorporating emojis, repetitive expressions, and the nuances of complex hashtags.

Consequently, two core indicators were derived to evaluate each tourist destination:

Evaluation Model: Rank-Based Scoring and Korea’s Top 500

Buzz Volume is an absolute metric ranging from tens of thousands to millions, while Sentiment Ratio is a relative metric ranging from 0 to 100%. Directly combining two indicators with different units and scales may result in statistical distortion. For example, mega-destinations with immense buzz volume could be disproportionately favored due to the sheer weight of absolute numbers even with lower sentiment ratios, whereas destinations with low buzz but high satisfaction could be undervalued.

To address this, we designed a hybrid evaluation model based on relative rankings rather than absolute figures. This method places values of different units on the "same scale," allowing for a comparable assessment of both famous landmarks and hidden gems.

The specific procedures are as follows:

This model enables fair evaluation on an equal footing between large-scale destinations with overwhelming recognition (e.g., mega theme parks in the metropolitan area) and small-scale regional spots with lower recognition but high satisfaction (e.g., local arboretums, trekking courses, observatories). In essence, it is a structure designed to capture both "famous places" and "beloved places" simultaneously.

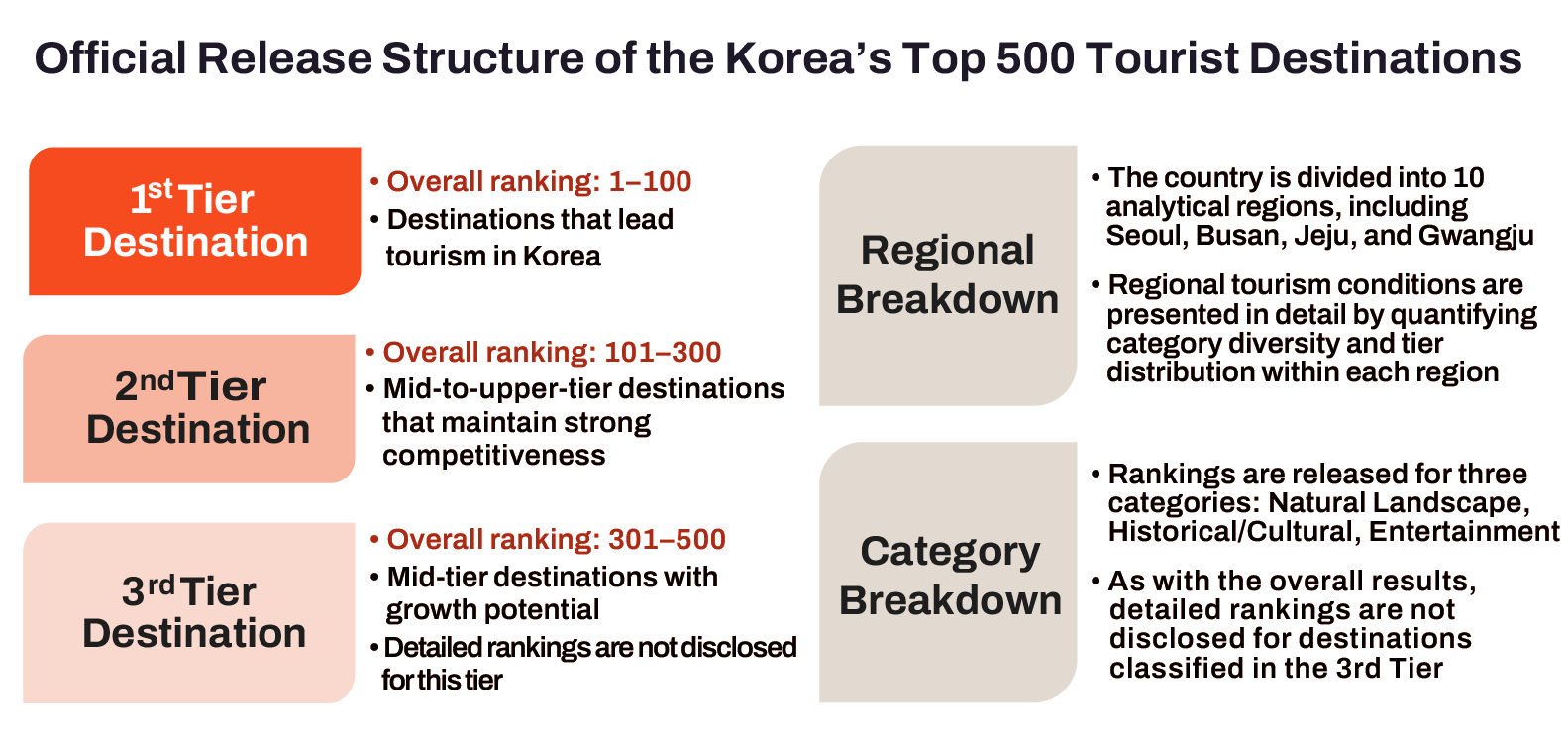

Based on the final calculated composite rankings, this study selected the top 500 tourist destinations (“Korea’s Top 500”). To enhance their utility for policy and industry applications, these destinations were classified and announced in a three-tier system. This distinction serves not merely as a hierarchy but as an “actionable classification” designed to differentiate policy inputs and growth strategies. Furthermore, as the analysis covered all basic local governments across the Republic of Korea, final adjustments were made to ensure that at least one tourist destination from each municipality was included in the final 500.

Analysis Results

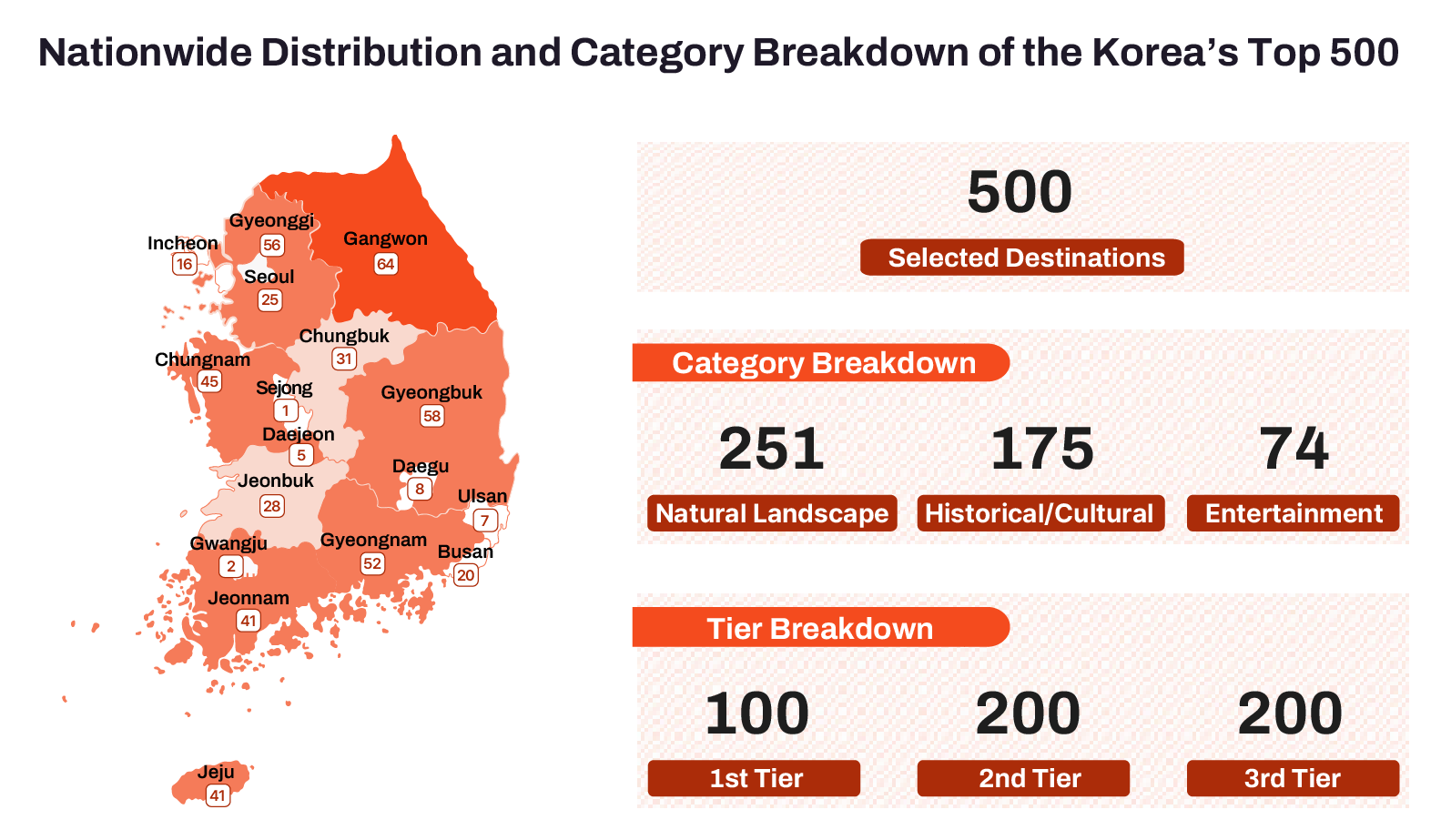

The analysis reveals that while traditional powerhouses such as Seoul, Jeju, and Busan continue to dominate the upper echelons, the marked emergence of small and medium-sized regional destinations signals promising potential for balanced regional tourism development. Above all, these findings demonstrate that the center of gravity in tourism is shifting—from destinations that are merely “famous” to those that are genuinely “beloved.” (Please refer to the appendix for the full list of Korea’s Top 500 Tourist Destinations.)

Composition of Korea’s Top 500: Nature as the Foundation, History as the Axis, and Entertainment as the Growth Engine

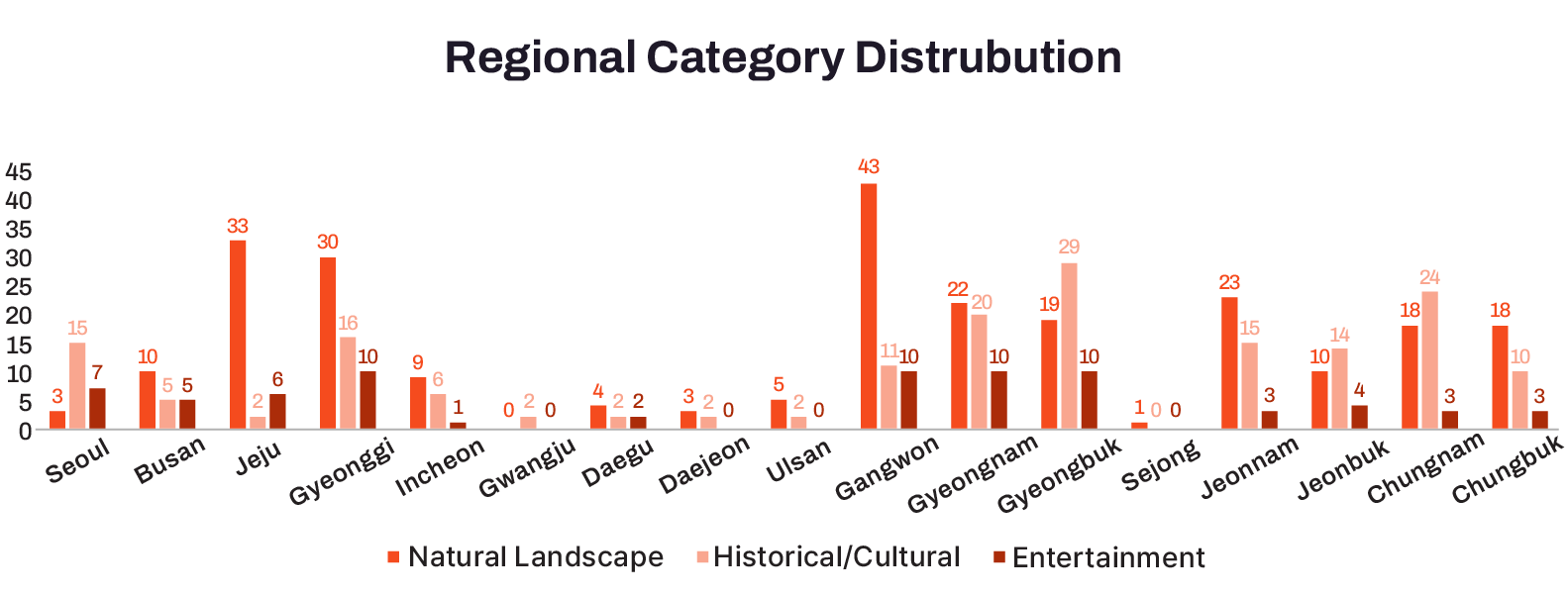

First, categorizing the 500 destinations into three sectors—Natural Landscape, Historical/Cultural, and Entertainment—reveals the underlying character of Korea’s representative tourist sites.

The Top 500 exhibits a structure where the Natural Landscape category accounts for the largest proportion, followed by the Historical/Cultural category. Meanwhile, the Entertainment category, though relatively smaller in absolute numbers, demonstrates significant impact within the upper rankings. This implies that the foundation of Korean tourism rests upon the demand for relaxation and healing derived from nature—mountains, seas, forests, and lakes. Simultaneously, it illustrates that the central axis defining the nation’s tourism identity and narrative is rooted in historical and cultural resources.

Although the Entertainment category is smaller in absolute terms, it holds immense strategic importance as it functions as an “accelerator”—facilitating experiences, consumption, and content creation to expedite the diffusion of tourism appeal.

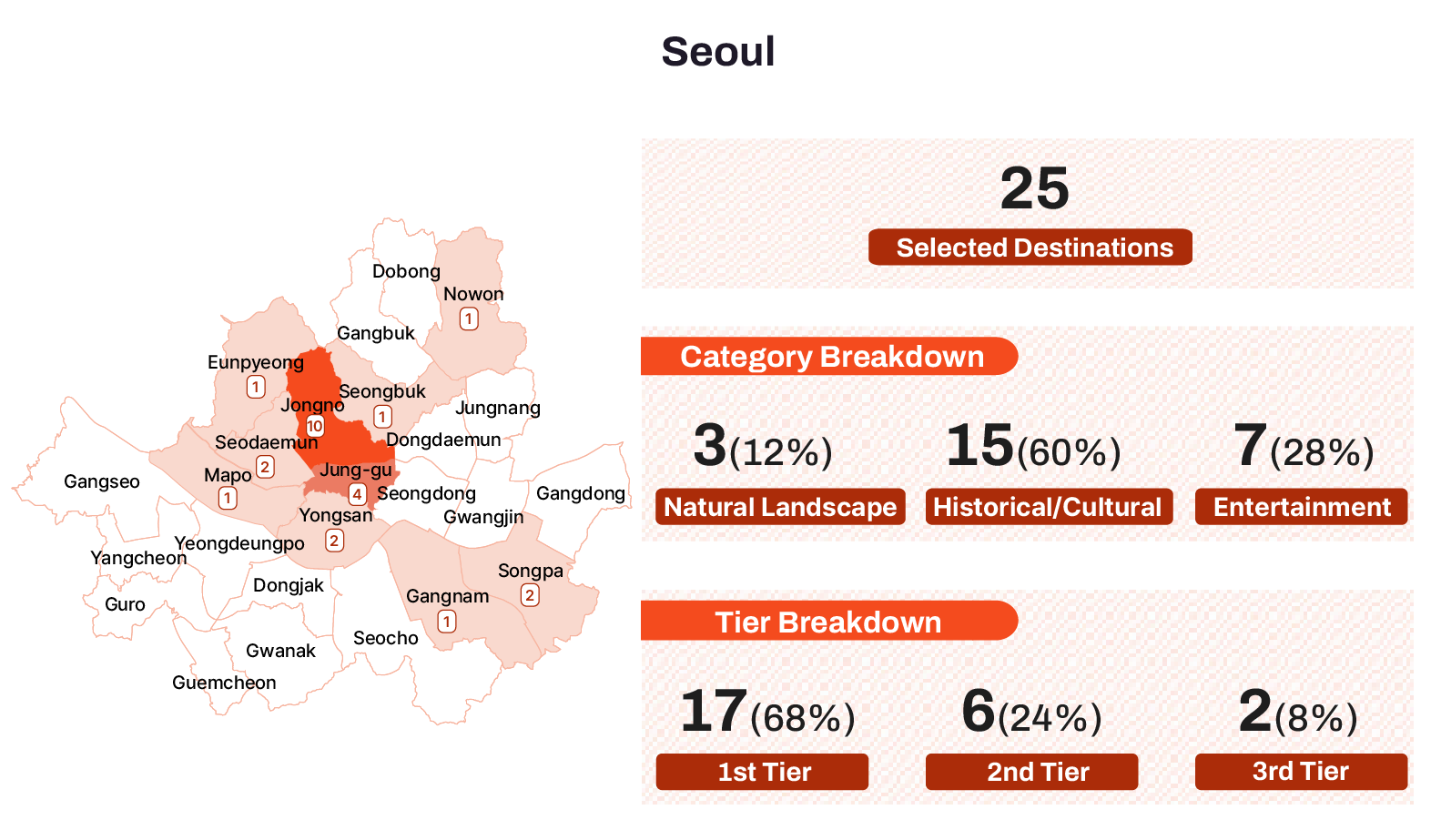

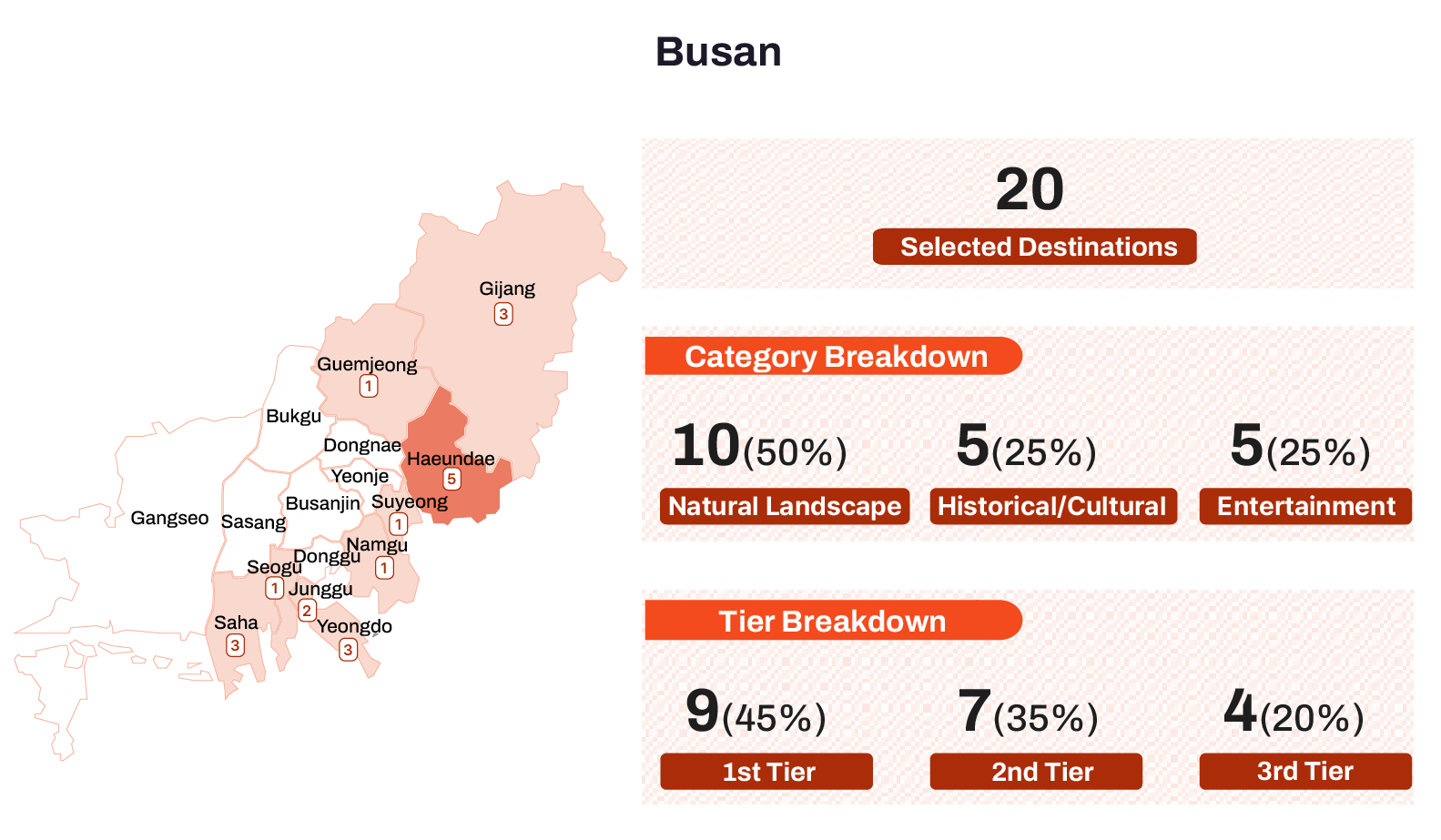

Regional Landscape: History in Seoul, Nature in Gangwon & Jeju, and Convergence in Busan

Next, examining the distribution by region reveals highly distinct tourism identities for each zone. Seoul emerges as a quintessential “Historical and Cultural Hub,” where historical and cultural resources are densely concentrated within the city center. Its upper rankings are driven by representative cultural heritage sites, museums, and urban cultural resources. Seoul’s strength lies not merely in the appeal of individual destinations but in the fact that these historical and cultural resources form a collective “cluster.” This demonstrates Seoul’s structural advantage as both the primary entry point for international tourists and the benchmark for domestic tourism.

In contrast, Gangwon and Jeju exhibit an overwhelmingly high proportion of Natural Landscape destinations. Gangwon serves as an ecological and leisure mecca possessing both mountains and seas, offering a wide array of choices on a national scale. Jeju demonstrates a high dependency on natural landscapes, further reinforcing its character as the “representative region for nature-based tourism.” However, this strength inherently implies a vulnerability to seasonality and meteorological variables, suggesting a strategic need to supplement these regions with weather-independent indoor content or stay-oriented experiential elements.

Busan is characterized by a convergent structure that centers on marine natural landscapes but integrates urban content, night tourism, and local culture. In essence, Busan illustrates an evolution into an “all-round tourism city” where urban experiences and consumption occur simultaneously, anchored by the powerful natural asset of the sea.

The Gyeongbuk region is characterized by the coexistence of robust historical and cultural resources, such as those in Gyeongju and Andong, alongside marine and natural resources in areas like Pohang and Uljin. This structural composition indicates significant potential for generating synergy through intra-regional linked tourism.

The Chungcheong and Jeolla regions display a relatively balanced portfolio of natural and historical/cultural resources rather than being skewed toward a specific typology. Consequently, strategies that interconnect differentiated regional narratives and experiences become increasingly critical for these areas.

Significance of Top Rankings by Category: What Makes a Champion?

A closer examination of the top-tier destinations by category clarifies "what travelers respond to." In the Natural Landscape category, while mountain, valley, and lake resources have traditionally been dominant, this year's results highlight a conspicuous presence of marine tourism destinations. Beaches are no longer mere static landscapes; when integrated with urban content, they transform into powerful stages for experience, facilitating rapid emotional diffusion. In essence, competition in the natural landscape sector is shifting from "who has the grander nature" to "who can create better scenes and experiences."

In the Historical/Cultural category, Seoul’s overwhelming dominance in the upper rankings is confirmed. This is not solely due to the intrinsic value of cultural heritage itself but is the result of combining accessibility, content creation, and the reconstruction of heritage into "experienceable narratives." Historical and cultural resources gain greater vitality and diffusion power when they go beyond mere preservation to integrate with night tours, traditional costume experiences, and events.

The Entertainment category is dominated by high-precision hardware content such as theme parks and experiential facilities. The advantage of this type lies in its clear experiential structure; high satisfaction leads to high probabilities of revisits and recommendations, and, crucially, it reliably provides "scenes convertible into photos and videos." This explains why the entertainment category, despite its smaller overall proportion, exhibits explosive power in the top rankings.

Three Representative Cases: Rankings Driven by Paradigm Shifts

The core of this year's top rankings lies in the transformation of how travelers consume places. The first case is Gwangalli Beach surpassing Haeundae Beach to take the overall No. 1 spot in "Korea's Top 500." While Haeundae has long been the symbol of "Korea's summer sea," Gwangalli can be defined as a space that has reconstructed the traveler experience by adding participatory content to its natural landscape. In particular, nighttime content like drone shows possesses powerful diffusion potential in the digital space, inducing travelers to immediately capture and share their on-site moments. If Haeundae is a space of "spectator-scale," Gwangalli functions as a "participatory stage" where travelers create scenes themselves, and this distinction is directly reflected in digital sentiment responses.

The second case is the rediscovery of Gyeongbokgung Palace. While it remains a top-tier destination in the historical/cultural sector, the mode of its consumption has changed. Hanbok (traditional dress) experiences and night tours have transformed cultural heritage from a "solemn space of observation" into an "immersive experience platform." When traditional assets are combined with modern presentation, historical tourism achieves both preservation and enjoyment, serving as a powerful attraction for both the younger generation and international tourists.

The third case is the rise of the provincial city shown by Pohang's Space Walk. Pohang was not traditionally a major tourist city, but the Space Walk created a nationwide sensation by combining iconic form, experientiality, panoramic views, and "content-ability" (shareability via photos/video). This demonstrates that even a city with relatively weaker historical or natural foundations can transform its image and reshape tourism flows with a single "killer content" possessing overwhelming visuals and unique experiences.

The analysis of "Korea's Top 500" indicates that Korean tourism is moving away from competition centered on large-scale infrastructure and symbolic landmarks toward a direction where travelers actively intervene and reproduce experiences. This signifies not a simple change in taste but a structural shift in how travelers evaluate and remember destinations.

The concept that comprehensively explains this transition is S.P.E.C.T.R.U.M.

S.P.E.C.T.R.U.M. is a trend framework encompassing eight flows penetrating Korean tourism in 2025: Specialized, Personalized, Eco-friendly, Connected, Tech-based, Rural, Unique, and Meaningful. At the center of this framework lies not the question "How famous is it?" but the criterion "Is it meaningful, does it fit me, and is it an experience I want to talk about again?"

Synthesizing the data from 500 destinations and qualitative analysis, three trends among these stand out distinctly.

1. Choncance: The Moment the Countryside Becomes a ‘Destination’ (Rural · Meaningful) The first core trend is "Choncance" (Chon [countryside] + Vacance), which has spread primarily among the MZ generation. This goes beyond a simple retro fad to show that the countryside is being redefined not as a stopover or a space for the parents' generation, but as an intentionally selected travel destination. Data shows a steady rise in positive sentiment ratios for rural, Hanok, and village-experience destinations. Places like "Grandma House" in Namyangju and "Chosimae Hanok Stay" in Yangpyeong are experiencing booking wars despite having more inconveniences compared to luxury hotels. Elements like traditional kitchens, "mon-pe" (baggy farming pants), and rustic country tables, once symbols of deficiency, are now perceived as scarce emotional resources unavailable in the city. The root cause is fatigue from the hyper-digital environment and competitive society. Travelers crave recovery and emotional rest in less stimulating environments rather than seeking more stimulation. Choncance provides "time where doing nothing is okay," and this experience is reflected in very high favorability in digital sentiment data. In short, the slowness and simplicity of the countryside are converting from weaknesses into powerful competitive advantages.

2. Hyper-Localism: Traveling to Stay in ‘Localness’ (Specialized · Personalized · Unique) The second core trend is Hyper-Localism. This refers to a travel style that moves away from "stamp-tour style" consumption of famous sites and delves deep into the unique life and stories of a region. Travelers now value "what they experienced and felt there" more than "where they went." This flow is confirmed in data-driven policy cases. Gimpo City, instead of vague image promotion, designed the "Gimpo 5 Flavors Road" by fusing credit card payment data and mobile carrier movement data to identify restaurants and routes where actual consumption concentrates. This was tourism design based on evidence, not intuition, weaving local gastronomy and life stories into a narrative. Consequently, Gimpo began to be recognized not as a simple satellite city of Seoul but as a meaningful local gastronomic destination. The core of hyper-localism lies not in large-scale development but in the ability to sophisticatedly interpret and narrate existing regional resources. When local food, lifestyles, alleyway atmospheres, and people's expressions are woven into a single experience, traveler sentiment scores are maximized. This shows that the condition for a destination to be beloved is the combination of "Specialized" and "Personalized."

3. The Paradox of Smart Tourism: High-Tech for Analog Sentiment (Tech-based · Connected) The third trend appears paradoxical. To enjoy the most analog travel—such as Choncance or local stay-oriented travel—travelers demand the most sophisticated digital technology. However, technology here must operate as "invisible infrastructure" that removes travel inconveniences rather than appearing as the protagonist. Incheon Metropolitan City's Smart Tourism City project illustrates this direction. The "Incheon e-G" app visualizes the past of the Open Port area using AR, recommends personalized courses via AI, and enables "hands-free travel" through luggage delivery services. Travelers do not strongly perceive the presence of technology, but as a result, immersion and convenience are significantly enhanced. This case suggests that technology should be a means to not disrupt the experience, not the purpose of tourism itself. The ultimate goal of smart tourism is not to show off more functions but to help travelers focus more deeply on the space and the moment.

In conclusion, the tourism trend of 2025, summarized as S.P.E.C.T.R.U.M., dictates that being famous is no longer enough. A destination gains competitiveness only when travelers intervene in the space, feel emotions, and want to speak about it again. While natural landscapes remain the foundation of Korean tourism, sentiment diffusion does not occur without the combination of scenes, narratives, and participatory experiences. Historical and cultural resources also gain sustainable vitality only when reinterpreted with modern sensibilities beyond preservation. Ultimately, tourism competitiveness depends not on "how many people came," but on "how many people talk about that experience again."

Currently, tourism policies in many local governments are still driven by "tangible short-term outcomes." Infrastructure-centric projects such as suspension bridges, cable cars, observatories, and monorails may generate short-term buzz; however, without sufficient feasibility studies and differentiation strategies, they risk resulting in budget waste and subsequent neglect. The fundamental issue lies not in the facilities themselves, but in "Me-too" imitative strategies that are disconnected from the local context.

Tourists do not deliberately visit a region to see "something that exists everywhere". Installing a suspension bridge simply because a neighboring district has one is an approach that, in the long term, erodes the region's unique color and leads to a downward leveling of tourism appeal. Local governments and DMOs (Destination Marketing/Management Organizations) must now shift away from construction-centric thinking and transform into "planning-centric organizations" focused on elevating the quality of the travel experience.

Furthermore, they must abandon the notion of developing all tourist sites within a region simultaneously; instead, they should distinguish between core destinations and supporting destinations, clearly defining their respective roles. In this process, the most critical investment target is not facilities but people—namely, Humanware such as local creators, commentators, and planners who can excavate and interpret local stories. In essence, tourism differentiation stems not from concrete, but from narratives and people.

2. Develop ‘Only-Here’ Content: Start from Regional DNA

The core of tourism competitiveness is now "Only-Here Content"—experiences that are possible exclusively in that specific region. This is also critical from the perspective of the Information Adoption Model (IAM). When travelers accept tourism information, the decisive factor is not the size of the information source but the "Argument Quality," or the intrinsic attractiveness of the content itself.

Pohang’s Space Walk is a case where the regional identity of an industrial city was transformed through creative inversion, sublimating the city’s DNA of steel structures into tourism content. Suncheon City established an ecological tourism brand by linking the Suncheonman Bay National Garden with its wetlands, while Tongyeong City has cultivated the image of an "Island of Arts" by consistently nurturing the Tongyeong International Music Festival for over 20 years. The commonality among these regions is that they started not from facilities, but from stories and identity.

3. Data-Driven ‘Precision Targeting’ and Strengthening DMO Collaboration

Another structural issue is the inefficiency of tourism marketing. Many local governments repeatedly use limited budgets to promote to an unspecified majority with generic "Come to our region" messages. This approach yields low efficiency and easily leads to budget waste.

The solution is data-driven precision targeting. Utilizing the Buzz Volume and Sentiment Score data established in this study, tourist destinations can be categorized into quadrants such as "High Reputation/Low Attraction" and "Low Reputation/High Attraction". For the former, it is desirable to focus on improving service quality and satisfaction rather than additional promotion; the latter can be considered "hidden gems" capable of sufficient growth through word-of-mouth strategies without large-scale advertising.

Therefore, DMOs must understand this "Reputation–Attraction Matrix" and practically apply it to policy formulation and marketing decision-making processes. At the same time, there is a need to actively leverage private sector technological capabilities, such as personalized recommendations and interest-based advertising, through collaboration with OTAs (Online Travel Agencies) and platform companies. Essentially, a division of roles and cooperation is required where the public sector strengthens data interpretation and regional planning capabilities, while the private sector combines diffusion and conversion (booking, payment, recommendation) technologies.

4. The Private Sector: Hyper-Personalized Products and Bridging the Digital Divide

There is a clear opportunity for the private industry. The "Korea’s Top 500" data reveals niche demands that have not yet been fully utilized in the market. Travel agencies and OTAs need to move beyond products centered on Tier 1 destinations and develop hyper-personalized products that weave together Tier 2 and Tier 3 destinations with high sentiment scores. For instance, thematic products like "Healing spots only I know" or "Instagrammable Choncance tours" can generate higher satisfaction and loyalty than mass tourism.

Additionally, large platform companies need to expand technological partnerships and support to enable small-scale regional destinations, which lack technological infrastructure, to acquire reservation, payment, and information provision systems. This is a pathway to mitigate information asymmetry caused by the Matthew Effect and enhance the overall sustainability of the tourism ecosystem.

is not a simple ranking table. It is a new compass, retrieved from the sea of data, pointing toward the direction in which Korean tourism must advance. This study tracked not the "scale" or "facilities" of tourist sites, but where the traveler's heart moves and stays. The results are clear. The data explicitly demonstrates that a small drone show gathers more people than massive infrastructure, an old rural house delivers deeper emotion than a state-of-the-art hotel, and a discarded steel structure can be reborn as a city's symbol (Pohang).

The choice is now clear. Will we continue to exhaust budgets and await decline by remaining buried in hardware construction according to past inertia, or will we transition to "tourism that designs appeal" by reading traveler sentiment in the direction pointed to by data? The solution to breaking through the crisis facing Korean tourism lies not in building more facilities, but in designing experiences where travelers intervene, narrate, and want to revisit.

"Korea’s Top 500" shows that this change has already begun in the field. The 100 destinations selected in Tier 1 have established themselves as beloved sites through content and experience, while the remaining 400 destinations in Tiers 2 and 3 are accumulating potential and preparing to leap forward in their own ways. What matters is not the hierarchy but the direction; not the ranking but the strategy.

Now, it is time for policies and systems to follow this change. The performance of tourism policy should no longer be evaluated by the number of completed buildings, but by the density of stories remaining in people's memories and conversations. We hope that the data and strategies presented in this report will permeate the field, allowing every corner of Korea to be reborn not as a "place visited once," but as a "place retold and revisited." That is the path for the sustainable growth of Korean tourism, and the destination to which this new compass points.

Reference

Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. MIT Press.

Sussman, S. W., & Siegal, W. S. (2003). Informational influence in organizations: An integrated approach to knowledge adoption. Information Systems Research, 14(1), 47–65.

1st Tier

| Rank | Local Governments | Tourist Destinations |

| 1 | Busan Suyeong | Gwangalli Beach |

| 2 | Busan Haeundae | Haeundae Beach |

| 3 | Seoul Songpa | Lotte World |

| 4 | Gyeonggi Yongin | Everland |

| 5 | Seoul Jongno | Gyeongbokgung Palace |

| 6 | Seoul Jongno | Bukchon Hanok Village |

| 7 | Seoul Yongsan | National Museum of Korea |

| 8 | Jeonbuk Jeonju | Jeonju Hanok Village |

| 9 | Seoul Jung | Deoksugung Palace |

| 10 | Jeju Seogwipo | Seongsan Ilchulbong |

| 11 | Jeju Jeju | Udo Island |

| 12 | Seoul Jongno | Changdeokgung Palace |

| 13 | Gyeonggi Gwacheon | Seoul Land |

| 14 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Bulguksa Temple |

| 15 | Seoul Jongno | Changgyeonggung Palace |

| 16 | Seoul Yongsan | N Seoul Tower |

| 17 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Cheomseongdae Observatory |

| 18 | Gyeonggi Suwon | Hwaseong Fortress |

| 19 | Seoul Songpa | Lotte World Tower |

| 20 | Seoul Jongno | Ikseon-dong |

| 21 | Gangwon Chuncheon | Nami Island |

| 22 | Gyeonggi Gwangju | Namhansanseong Fortress |

| 23 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Gyeongju World |

| 24 | Jeonnam Suncheon | Suncheon Bay Wetland Reserve |

| 25 | Incheon Yeonsu | Songdo Central Park |

| 26 | Incheon Jung | Open Port Area (Incheon Chinatown) |

| 27 | Gyeongnam Yangsan | Tongdosa Temple |

| 28 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Seokguram Grotto |

| 29 | Incheon Jung | Wolmido Island |

| 30 | Gangwon Gangneung | Jeongdongjin |

| 31 | Gyeongbuk Andong | Hahoe Folk Village |

| 32 | Gangwon Sokcho | Seoraksan National Park |

| 33 | Seoul Jung | Myeongdong Cathedral |

| 34 | Daegu Jung | Seomun Market |

| 35 | Gyeonggi Yangpyeong | Dumulmeori |

| 36 | Gyeonggi Hwaseong | Jebudo Island |

| 37 | Gangwon Hongcheon | Vivaldi Park |

| 38 | Gyeongnam Hapcheon | Haeinsa Temple |

| 39 | Gyeongbuk Andong | Byeongsan Seowon |

| 40 | Gyeonggi Gwangju | Hwadam Forest |

| 41 | Seoul Jung | Gyeonghuigung Palace |

| 42 | Gyeonggi Gapyeong | Jara Island |

| 43 | Gangwon Gangneung | Gyeongpodae Pavilion |

| 44 | Seoul Seodaemun | Independence Gate |

| 45 | Seoul Jongno | Insadong-gil |

| 46 | Daejeon Daedeok | Daecheong Lake |

| 47 | Chungbuk Chungju | Chungju Lake |

| 48 | Jeonnam Gurye | Hwaeomsa Temple |

| 49 | Gyeonggi Yongin | Korean Folk Village |

| 50 | Jeju Jeju | Hyeopjae Beach |

| 51 | Chungnam Boryeong | Daecheon Beach |

| 52 | Gyeonggi Anseong | Anseong Farmland |

| 53 | Gyeongbuk Pohang | Homigot Cape |

| 54 | Gyeongbuk Pohang | Yeongildae Beach |

| 55 | Gangwon Yangyang | Naksansa Temple |

| 56 | Busan Haeundae | Dongbaekseom Island |

| 57 | Busan Jung | Jagalchi Market |

| 58 | Jeju Seogwipo | Seopjikoji |

| 59 | Busan Haeundae | Songjeong Beach |

| 60 | Gyeongnam Jinju | Jinjuseong Fortress |

| 61 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Daereungwon Tomb Complex |

| 62 | Gyeongbuk Pohang | Jukdo Market |

| 63 | Jeju Seogwipo | Gotjawal Provincial Park |

| 64 | Gangwon Sokcho | Yeongnangho Lake |

| 65 | Gyeonggi Pocheon | Korea National Arboretum |

| 66 | Gyeongnam Hadong | Hwagae Market |

| 67 | Gyeonggi Pocheon | Sanjeong Lake |

| 68 | Gangwon Gangneung | Anbandae |

| 69 | Chungnam Gongju | Donghaksa Temple |

| 70 | Busan Geumjeong | Beomeosa Temple |

| 71 | Chungbuk Jecheon | Uirimji Reservoir |

| 72 | Jeonnam Yeosu | Odongdo Island |

| 73 | Gyeongnam Jinju | Jinyang Lake |

| 74 | Seoul Mapo | Hongdae Red Road |

| 75 | Jeju Jeju | Hamdeok Beach |

| 76 | Ulsan Ulju | Ganjeolgot Cape |

| 77 | Jeonnam Gurye | Nogodan Ridge |

| 78 | Gangwon Sokcho | Sokcho Beach |

| 79 | Gyeongbuk Pohang | Space Walk |

| 80 | Gangwon Gangneung | Gangmun Beach |

| 81 | Busan Gijang | Haedong Yonggungsa Temple |

| 82 | Jeju Seogwipo | Soesokkak |

| 83 | Jeonnam Suncheon | Suncheon Bay National Garden |

| 84 | Jeju Seogwipo | Jungmun Tourist Complex |

| 85 | Jeju Jeju | Biyangdo Island |

| 86 | Incheon Ongjin | Seonjaedo Island |

| 87 | Jeonnam Gwangyang | Maehwa Village |

| 88 | Gyeongnam Tongyeong | Yokjido Island |

| 89 | Seoul Jongno | Gwangjang Market |

| 90 | Gangwon Pyeongchang | Woljeongsa Temple |

| 91 | Gyeonggi Goyang | Haengju Fortress |

| 92 | Jeonnam Damyang | Juknokwon Bamboo Garden |

| 93 | Chungnam Taean | Chollipo Arboretum |

| 94 | Seoul Jongno | Naksan Park |

| 95 | Gangwon Sokcho | Dongmyeong Port |

| 96 | Gangwon Cheorwon | Goseokjeong Pavilion |

| 97 | Chungbuk Cheongju | Cheongnamdae |

| 98 | Busan Saha | Gamcheon Culture Village |

| 99 | Busan Saha | Eulsukdo Island |

| 100 | Jeonnam Goheung | Sorokdo Island |

2nd Tier

| Rank | Local Governments | Tourist Destinations |

|---|---|---|

| 101 | Chungnam Taean | Mallipo Beach |

| 102 | Incheon Jung | Silmido Island |

| 103 | Jeju Jeju | Witse Oreum |

| 104 | Chungbuk Chungju | Sujupalbong Peaks |

| 105 | Ulsan Jung | Taehwagang National Garden |

| 106 | Jeju Jeju | Yongyeon Valley |

| 107 | Busan Gijang | Osiria Tourist Complex |

| 108 | Chungnam Taean | Kkotji Beach |

| 109 | Chungnam Gongju | Gongsanseong Fortress |

| 110 | Jeonbuk Gochang | Seonunsa Temple |

| 111 | Jeonnam Suncheon | Songgwangsa Temple |

| 112 | Jeonbuk Muju | Hyangjeokbong Peak |

| 113 | Jeju Seogwipo | Yongmeori Coast |

| 114 | Daejeon Seo | Hanbat Arboretum |

| 115 | Gyeongnam Namhae | German Village |

| 116 | Chungnam Yesan | Sudeoksa Temple |

| 117 | Gangwon Goseong | Unification Observatory |

| 118 | Gyeongbuk Yeongju | Buseoksa Temple |

| 119 | Seoul Jung | Namsangol Hanok Village |

| 120 | Daejeon Yuseong | Yuseong Hot Springs |

| 121 | Gangwon Yangyang | Hajodae Pavilion |

| 122 | Gyeonggi Gwangmyeong | Gwangmyeong Cave |

| 123 | Jeonnam Yeosu | Hyangiram Hermitage |

| 124 | Jeju Seogwipo | Cheonjiyeon Waterfall |

| 125 | Gangwon Wonju | Museum SAN |

| 126 | Gyeongbuk Gimcheon | Jikjisa Temple |

| 127 | Seoul Seongbuk | Bukhansan National Park |

| 128 | Gangwon Gangneung | Ojukheon House |

| 129 | Chungnam Gongju | Royal Tomb of King Muryeong |

| 130 | Incheon Ganghwa | Jeondeungsa Temple |

| 131 | Daegu Dalseo | 83 Tower |

| 132 | Busan Saha | Dadaepo Beach |

| 133 | Gyeonggi Paju | Paju DMZ |

| 134 | Jeonbuk Iksan | Mireuksa Temple Site |

| 135 | Chungnam Seosan | Haemieupseong Fortress |

| 136 | Sejong Sejong | National Sejong Arboretum |

| 137 | Gyeongnam Namhae | Boriam Hermitage |

| 138 | Jeju Seogwipo | Camellia Hill |

| 139 | Gyeonggi Hwaseong | Jeongok Port |

| 140 | Gangwon Sokcho | Cheongcho Lake |

| 141 | Busan Yeongdo | Huinnyeoul Culture Village |

| 142 | Gyeongnam Changnyeong | Upo Wetland |

| 143 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Woljeonggyo Bridge |

| 144 | Daegu Suseong | Suseongmot Lake |

| 145 | Chungnam Buyeo | Gungnamji Pond |

| 146 | Jeonnam Suncheon | Naganeupseong Folk Village |

| 147 | Gyeongbuk Cheongdo | Unmunsa Temple |

| 148 | Jeonnam Yeosu | Geumodo Island |

| 149 | Gyeonggi Uiwang | Wangsong Lake |

| 150 | Busan Haeundae | Blueline Park |

| 151 | Jeonbuk Imsil | Okjeongho Lake |

| 152 | Chungbuk Danyang | Guinsa Temple |

| 153 | Chungnam Asan | Onyang Hot Springs |

| 154 | Gyeongnam Miryang | Pyochungsa Temple |

| 155 | Jeju Jeju | Gimnyeong Beach |

| 156 | Seoul Jongno | Unhyeongung Palace |

| 157 | Jeju Jeju | Geumneung Beach |

| 158 | Gyeonggi Yeoju | Silleuksa Temple |

| 159 | Gangwon Cheorwon | Cheorwon DMZ |

| 160 | Gyeongbuk Andong | Woryeonggyo Bridge |

| 161 | Gyeongbuk Gimcheon | Yeonhwaji Pond |

| 162 | Gangwon Pyeongchang | Daegwallyeong Sheep Farm |

| 163 | Gyeongbuk Ulleung | Seonnyeotang Pool |

| 164 | Seoul Gangnam | COEX Aquarium |

| 165 | Chungbuk Danyang | Dodamsambong Peaks |

| 166 | Incheon Jung | Eulwangni Beach |

| 167 | Jeonnam Yeosu | Aqua Planet Yeosu |

| 168 | Jeonnam Suncheon | Seonamsa Temple |

| 169 | Gyeongnam Miryang | Ice Valley |

| 170 | Busan Yeongdo | Taejongdae Park |

| 171 | Gyeonggi Namyangju | Mului Garden |

| 172 | Gyeongnam Geoje | Windy Hill |

| 173 | Jeonbuk Buan | Naesosa Temple |

| 174 | Jeonbuk Namwon | Gwanghallu Garden |

| 175 | Jeonnam Haenam | Daeheungsa Temple |

| 176 | Gangwon Hongcheon | Ocean World |

| 177 | Jeju Jeju | Seoubong Peak |

| 178 | Seoul Eunpyeong | Eunpyeong Hanok Village |

| 179 | Jeju Seogwipo | Jeongbang Waterfall |

| 180 | Chungnam Yesan | Yedangho Lake |

| 181 | Gangwon Chuncheon | Kim You-jeong Rail Bike |

| 182 | Ulsan Dong | Ilsan Beach |

| 183 | Gangwon Gangneung | ARTE Museum Gangneung |

| 184 | Gyeonggi Pocheon | Herb Island |

| 185 | Gyeongnam Hadong | Jirisan National Park |

| 186 | Jeju Jeju | Bijarim Forest |

| 187 | Jeju Jeju | Iho Tewoo Beach |

| 188 | Jeju Jeju | Panpo Port |

| 189 | Daegu Dalseo | Daegu Arboretum |

| 190 | Gyeongbuk Andong | Dosan Seowon |

| 191 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Tomb of King Munmu |

| 192 | Gyeongnam Namhae | Darangyi Village |

| 193 | Busan Yeongdo | ARTE Museum Busan |

| 194 | Jeonbuk Gochang | Sangha Farm |

| 195 | Gangwon Sokcho | Abai Village |

| 196 | Jeju Jeju | Halla Arboretum |

| 197 | Chungbuk Danyang | Gosu Cave |

| 198 | Jeju Jeju | Gwakji Beach |

| 199 | Daejeon Yuseong | Sutonggol Valley |

| 200 | Gyeongnam Gimhae | Bongha Village |

| 201 | Jeju Jeju | ARTE Museum Jeju |

| 202 | Gyeongnam Hadong | Ssanggyesa Temple |

| 203 | Jeju Seogwipo | Aqua Planet Jeju |

| 204 | Jeju Seogwipo | Gwangchigi Beach |

| 205 | Gyeonggi Paju | Heyri Art Village |

| 206 | Incheon Ganghwa | Dongmak Beach |

| 207 | Chungnam Seocheon | National Institute of Ecology |

| 208 | Chungnam Buyeo | Nakhwaam Rock |

| 209 | Jeju Jeju | Yongduam Rock |

| 210 | Chungbuk Cheongju | Sangdangsanseong Fortress |

| 211 | Jeonnam Damyang | Gwanbangjerim Forest |

| 212 | Chungnam Buyeo | Jeongnimsa Temple Site |

| 213 | Gyeonggi Suwon | Ilwol Arboretum |

| 214 | Gyeongbuk Andong | Manhyujeong Pavilion |

| 215 | Chungbuk Boeun | Beopjusa Temple |

| 216 | Chungnam Asan | Dogo Hot Springs (Paradise Spa Dogo) |

| 217 | Chungnam Asan | Asan Hot Springs (Asan Spavis) |

| 218 | Gangwon Samcheok | Daeri Cave District |

| 219 | Chungnam Buyeo | Buyeo National Museum |

| 220 | Gyeonggi Pocheon | Art Valley |

| 221 | Jeju Jeju | Hallasan National Park |

| 222 | Gyeongnam Hamyang | Sangnim Park |

| 223 | Gangwon Gangneung | Haslla Art World |

| 224 | Gangwon Chuncheon | LEGOLAND Korea |

| 225 | Gyeonggi Yangju | Hoeamsa Temple Site |

| 226 | Gyeonggi Gapyeong | Petite France |

| 227 | Jeonnam Jangseong | Baekyangsa Temple |

| 228 | Chungbuk Chungju | Tangeumdae Pavilion |

| 229 | Chungnam Seosan | Gaesimsa Temple |

| 230 | Incheon Jung | Songwol-dong Fairy Tale Village |

| 231 | Chungnam Buyeo | Baekje Cultural Land |

| 232 | Gangwon Goseong | Hwajinpo Beach |

| 233 | Jeonbuk Gunsan | Gyeongam-dong Railway Village |

| 234 | Gyeongnam Hapcheon | Film Theme Park |

| 235 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Bomun Tourist Complex |

| 236 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Yangdong Folk Village |

| 237 | Gyeongbuk Yeongju | Sosu Seowon |

| 238 | Gyeonggi Osan | Mulhyanggi Arboretum |

| 239 | Chungbuk Danyang | Mancheonha Skywalk |

| 240 | Jeonnam Gokseong | Seomjin River Train Village |

| 241 | Busan Gijang | Ilgwang Beach |

| 242 | Jeonbuk Imsil | Imsil Cheese Theme Park |

| 243 | Gyeonggi Yangpyeong | Yongmunsa Temple |

| 244 | Chungnam Asan | Oeam Folk Village |

| 245 | Seoul Seodaemun | Seodaemun Prison History Hall |

| 246 | Jeju Seogwipo | Osulloc Tea Museum |

| 247 | Gangwon Donghae | Mureung Byeolyucheonji |

| 248 | Jeonbuk Gochang | Gochang Eupseong Fortress |

| 249 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Bunhwangsa Temple |

| 250 | Gyeongnam Tongyeong | Gangguan Harbor |

| 251 | Gyeonggi Gapyeong | Petite France |

| 252 | Jeonnam Jangseong | Baekyangsa Temple |

| 253 | Chungbuk Chungju | Tangeumdae Pavilion |

| 254 | Chungnam Seosan | Gaesimsa Temple |

| 255 | Incheon Jung | Songwol-dong Fairy Tale Village |

| 256 | Chungnam Buyeo | Baekje Cultural Land |

| 257 | Gangwon Goseong | Hwajinpo Beach |

| 258 | Jeonbuk Gunsan | Gyeongam-dong Railway Village |

| 259 | Gyeongnam Hapcheon | Film Theme Park |

| 260 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Bomun Tourist Complex |

| 261 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Yangdong Folk Village |

| 262 | Gyeongbuk Yeongju | Sosu Seowon |

| 263 | Gyeonggi Osan | Mulhyanggi Arboretum |

| 264 | Chungbuk Danyang | Mancheonha Skywalk |

| 265 | Jeonnam Gokseong | Seomjin River Train Village |

| 266 | Busan Gijang | Ilgwang Beach |

| 267 | Jeonbuk Imsil | Imsil Cheese Theme Park |

| 268 | Gyeonggi Yangpyeong | Yongmunsa Temple |

| 269 | Chungnam Asan | Oeam Folk Village |

| 270 | Seoul Seodaemun | Seodaemun Prison History Hall |

| 271 | Jeju Seogwipo | Osulloc Tea Museum |

| 272 | Gangwon Donghae | Mureung Byeolyucheonji |

| 273 | Jeonbuk Gochang | Gochang Eupseong Fortress |

| 274 | Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Bunhwangsa Temple |

| 275 | Gyeongnam Tongyeong | Gangguan Harbor |

| 276 | Gyeongnam Sacheon | Aerospace Museum |

| 277 | Gyeonggi Yeoju | Tomb of King Sejong |

| 278 | Jeonbuk Jinan | Tapsa Temple (Maisan) |

| 279 | Gangwon Gangneung | Sageunjin Beach |

| 280 | Gangwon Samcheok | Samcheok Beach |

| 281 | Chungnam Buyeo | Busosanseong Fortress |

| 282 | Jeju Jeju | Sangumburi Crater |

| 283 | Gangwon Cheorwon | Workers’ Party Headquarters |

| 284 | Gyeongnam Changwon | Robot Land |

| 285 | Gangwon Chuncheon | Samaksan Lake Cable Car |

| 286 | Gyeongnam Hadong | Samseonggung Shrine |

| 287 | Gyeonggi Pocheon | Bidulginang Falls |

| 288 | Gyeongbuk Cheongsong | Jusanji Reservoir |

| 289 | Gyeongnam Hadong | Choi Champandaek House |

| 290 | Jeonbuk Jeonju | Jeonju Hyanggyo |

| 291 | Gyeongnam Gimhae | Royal Tomb of King Suro |

| 292 | Chungbuk Chungju | Suanbo Hot Springs |

| 293 | Gyeonggi Anseong | Anseong Matchum Land |

| 294 | Gyeongnam Gimhae | Gimhae Lotte Water Park |

| 295 | Gangwon Donghae | Chotdaebawi Rock |

| 296 | Chungnam Hongseong | Namdang Port |

| 297 | Gyeongnam Sacheon | Sacheon Sea Cable Car |

| 298 | Gyeongbuk Yeongju | Museom Village |

| 299 | Chungbuk Yeongdong | Wollyubong Peak |

| 300 | Gyeongbuk Pohang | Bogyeongsa Temple |

3rd Tier (alphabetical order)

| Local Governments | Tourist Destinations |

|---|---|

| Chungnam Yesan | Agroland |

| Gyeongnam Haman | Agyang Ecological Park |

| Chungnam Cheongyang | Alps Village |

| Chungnam Dangjin | Ammi Art Museum |

| Gyeongnam Sacheon | Aramaru Aquarium |

| Jeonnam Yeosu | ARTE Museum Yeosu |

| Gangwon Goseong | Ayajin Beach |

| Gyeonggi Bucheon | Azalea Hill |

| Gyeongbuk Bonghwa | Baekdudaegan National Arboretum |

| Chungbuk Eumseong | Baekya Natural Recreation Forest |

| Jeonbuk Namwon | Baemsagol Valley |

| Chungbuk Jecheon | Baeron Catholic Shrine |

| Jeonbuk Muju | Bandiland |

| Gyeongbuk Gyeongsan | Bangokji |

| Ulsan Ulju | Bangudae Petroglyphs |

| Chungbuk Jeungpyeong | Bicycle Park |

| Jeonnam Wando | Bogildo Island (Seyeonjeong Pavilion) |

| Incheon Ganghwa | Bomunsa Temple |

| Gyeonggi Namyangju | Bongseonsa Temple |

| Jeonnam Boseong | Boseong Green Tea Fields |

| Busan Jung | Bosudong Book Street |

| Chungbuk Jincheon | Botapsa Temple |

| Gyeonggi Uijeongbu | Budae Jjigae Street |

| Gyeongnam Changnyeong | Bugok Hot Springs |

| Gyeongbuk Uljin | Bulyeong Valley |

| Gangwon Hwacheon | Bungeo Island |

| Gyeongnam Gimhae | Bunsanseong Fortress |

| Busan Haeundae | Busan Aquarium |

| Chungbuk Okcheon | Busodamak |

| Seoul Nowon | Butterfly Garden |

| Gyeonggi Paju | Byeokchoji Arboretum |

| Jeonbuk Gimje | Byeokgolje Reservoir |

| Gyeongbuk Cheongdo | Cheongdo Eupseong Fortress |

| Jeonnam Gwangyang | Cheongmaesil Farm |

| Gangwon Yeongwol | Cheongnyeongpo |

| Chungnam Taean | Cheongpodae Beach |

| Chungbuk Jecheon | Cheongpungho Cable Car |

| Chungnam Taean | Cheongsan Arboretum |

| Gyeonggi Anseong | Chiljangsa Temple |

| Incheon Ganghwa | Chojijin Fort |

| Gangwon Donghae | Chuam Beach |

| Chungnam Seocheon | Chunjangdae Beach |

| Chungnam Boryeong | Coal Museum |

| Daejeon Yuseong | Currency Museum |

| Jeonnam Jangheung | Cypress Forest Woodland |

| Jeonnam Sinan | Dadohaehaesang National Park |

| Jeonbuk Wanju | Daea Arboretum |

| Chungnam Geumsan | Daedunsan Provincial Park |

| Gyeongbuk Goryeong | Daegaya Tumuli |

| Chungbuk Danyang | Danyang Danuri Aquarium |

| Incheon Jung | Dapdong Cathedral |

| Gyeongbuk Uljin | Deokgu Hot Springs |

| Chungnam Yesan | Deoksan Hot Springs |

| Gyeonggi Dongducheon | Design Art Village |

| Gyeongnam Tongyeong | Dipirang |

| Gangwon Donghae | Dochebi Gol Sky Valley |

| Gyeonggi Osan | Doksanseong Fortress |

| Jeonnam Hwasun | Dolmen Site |

| Jeonnam Hampyeong | Dolmeori Beach |

| Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Donggung Palace and Wolji Pond |

| Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Donggungwon Garden |

| Gyeongnam Tongyeong | Dongpirang Village |

| Jeju Jeju | Eco Land Theme Park |

| Jeju Jeju | Eoseungsaeng Peak |

| Jeonbuk Jinan | Eunsusa Temple |

| Gyeonggi Paju | First Garden |

| Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Gameunsa Temple Site |

| Jeonbuk Sunchang | Gangcheonsan County Park |

| Incheon Ganghwa | Ganghwa Luge |

| Gyeonggi Gapyeong | Gapyeong Sheep Farm |

| Gangwon Jeongseon | Gariwangsan Cable Car |

| Gyeongbuk Chilgok | Gasan Supia |

| Jeonnam Gangjin | Gawudo Island |

| Gyeongnam Gimhae | Gaya Land |

| Gyeongnam Gimhae | Gaya Theme Park |

| Gyeongnam Hapcheon | Gayasan National Park |

| Gyeongnam Geochang | Geochang Changpowon |

| Gangwon Taebaek | Geomnyongso Spring |

| Gyeongbuk Gumi | Geumoland |

| Chungnam Gyeryong | Goemokjeong Pavilion |

| Chungnam Asan | Gongsere Cathedral |

| Chungbuk Danyang | Gudambong Peak |

| Gyeongnam Geoje | Gujora Beach |

| Gyeonggi Guri | Guri Tower |

| Gyeonggi Hanam | Gusanseong Shrine |

| Gyeonggi Anyang | Gwanak Arboretum |

| Chungnam Nonsan | Gwanchoksa Temple |

| Gyeonggi Siheung | Gwangokji |

| Gyeongbuk Sangju | Gyeongcheondae Pavilion |

| Gyeongbuk Seongju | Gyeongsan-ri Seongbak Forest |

| Daegu Jung | Gyesan Cathedral |

| Jeju Jeju | Haenyeo Museum |

| Gangwon Donghae | Haerang Observatory |

| Gyeongnam Geoje | Hallyeohaesang National Park |

| Jeonnam Yeosu | Hamel Lighthouse |

| Gyeongnam Hapcheon | Hapcheon Lake |

| Gyeongbuk Yecheon | Hoeryongpo |

| Jeonnam Muan | Hoesan White Lotus Pond |

| Gangwon Yangyang | Huhuam Temple |

| Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Hwangnyongsa Temple Site |

| Gyeonggi Yeoju | Hwangpo Sailboat |

| Chungbuk Goesan | Hwayang Gugok Valley |

| Chungnam Cheonan | Independence Hall of Korea |

| Gangwon Chuncheon | Jade Garden |

| Jeonbuk Jangsu | Jangan Mountain County Park |

| Gyeongbuk Yeongdeok | Jangsa Beach |

| Gangwon Sokcho | Jangsa Port |

| Ulsan Nam | Jangsaengpo Whale Culture Special Zone |

| Gyeonggi Hwaseong | Jebudo Marine Cable Car |

| Gyeongnam Uiryeong | Jeongamnu Pavilion |

| Gwangju Dong | Jeonil Building 245 |

| Ulsan Ulju | Jinha Beach |

| Gyeongnam Changwon | Jinhaeru |

| Jeonnam Yeosu | Jinnamgwan Hall |

| Gyeongbuk Andong | Jjimdak Alley |

| Gyeongbuk Uiseong | Jomunguk Museum |

| Gyeongbuk Uljin | Jukbyeon Coastal Sky Rail |

| Gangwon Samcheok | Jukseoru Pavilion |

| Gangwon Gangneung | Jumunjin Port |

| Chungbuk Chungju | Jungangtap Historic Park |

| Jeju Seogwipo | Jusangjeolli Cliff |

| Gangwon Chuncheon | Kim You-jeong Literature Village |

| Jeju Seogwipo | Luna Fall |

| Chungbuk Boeun | Malti Pass |

| Gangwon Donghae | Mangsang Beach |

| Gyeongbuk Uljin | Mangyangjeong Pavilion |

| Jeju Jeju | Manjanggul Cave |

| Chungnam Taean | Mongsanpo Beach |

| Gyeonggi Seongnam | Moran Market |

| Chungnam Boryeong | Muchangpo Beach |

| Gyeonggi Ansan | Mugunghwa Arboretum |

| Gyeongnam Haman | Mujinjeong Pavilion |

| Gangwon Donghae | Mukho Lighthouse |

| Jeonnam Yeonggwang | Mulmusang Happiness Forest |

| Gyeongbuk Mungyeong | Mungyeong Saejae Provincial Park |

| Chungnam Seosan | Munsusa Temple |

| Gyeonggi Gimpo | Munsusanseong Fortress |

| Ulsan Ulju | Myeongseon Island |

| Jeonbuk Jeongeup | Naejangsan National Park |

| Jeonnam Naju | Naju Eupseong Fortress |

| Gangwon Yangyang | Namae Port |

| Jeonbuk Namwon | Namwon Tourist Complex |

| Gyeongbuk Ulleung | Nari Basin |

| Gyeongbuk Uljin | National Marine Science Museum |

| Chungnam Dangjin | Naval Ship Park |

| Jeonnam Mokpo | Nojeokbong Peak |

| Chungnam Boryeong | Ocheon Port |

| Gangwon Pyeongchang | Odaesan National Park |

| Gyeongnam Geoje | Oedo Botania |

| Chungbuk Danyang | Oksunbong Peak |

| Busan Nam | Oryukdo Skywalk |

| Gyeongbuk Gyeongsan | Palgongsan Gatbawi |

| Gangwon Yanggu | Paroho Lake |

| Gangwon Hoengseong | Pungsuwon Cathedral |

| Gyeonggi Pyeongtaek | Pyeongtaek Lake Tourist Complex |

| Gyeonggi Gunpo | Royal Azalea Hill |

| Gangwon Gangneung | Sacheonjin Beach |

| Chungbuk Danyang | Sainam Rock |

| Jeonnam Mokpo | Samhakdo Island |

| Jeonbuk Wanju | Samnye Culture & Arts Village |

| Jeju Jeju | Samseonghyeol |

| Gangwon Jeongseon | Samtan Art Mine |

| Jeju Jeju | Sanyangkeunenggot |

| Jeju Seogwipo | Sara Oreum |

| Daegu Gunwi | Sayuwon |

| Incheon Jung | Seaside Park |

| Seoul Jongno | Seochon Village |

| Gyeonggi Icheon | Seolbong Park |

| Gyeongnam Namhae | Seolli Skywalk |

| Gyeongbuk Yeongyang | Seonbawi Tourist Site |

| Gyeongbuk Uljin | Seongnyugul Cave |

| Chungnam Taean | Sinduri Beach |

| Chungnam Dangjin | Sinri Catholic Shrine |

| Jeonbuk Gunsan | Sinsi Island |

| Gangwon Sokcho | Sokcho Tourist & Fishery Market |

| Gyeongnam Tongyeong | Somaemuldo Island |

| Incheon Jung | Somuui Island |

| Busan Seo | Songdo Marine Cable Car |

| Chungbuk Boeun | Songnisan National Park |

| Gangwon Chuncheon | Soyanggang Skywalk |

| Daegu Dalseong | Spa Valley |

| Gyeongbuk Yeongcheon | Starlight Village |

| Chungbuk Cheongju | Suamgol |

| Gyeonggi Namyangju | Sujongsa Temple |

| Gyeongnam Sancheong | Suseonsa Temple |

| Gangwon Taebaek | Taebaeksan National Park |

| Gyeongbuk Gyeongju | Tongiljeon Hall |

| Jeonnam Haenam | Ttangkkeut Observatory |

| Jeonnam Jindo | Unrim Mountain Studio |

| Jeonbuk Iksan | Wanggung-ri Ruins |

| Chungbuk Yeongdong | Wine Tunnel |

| Jeonnam Yeongam | Wolchulsan Gichan Land |

| Gangwon Inje | Wondae-ri Birch Forest |

| Gyeongbuk Gumi | Yaksaaam Hermitage |

| Gwangju Nam | Yangnim-dong History & Culture Village |

| Gyeongbuk Yeongdeok | Yeongdeok Snow Crab Street |

| Gyeonggi Suwon | Yeongheung Arboretum |

| Chungnam Yesan | Yesan Oriental Stork Park |

| Gangwon Donghae | Yongchu Waterfall |

| Jeonnam Boseong | Yulpo Beach |