The Future of the Golf Industry: Demographics and Macroeconomic Trends

Kwanyoung Lee / Associate Research Fellow, Yanolja Research / [email protected]

Yanolja Research previously examined the surge in golf demand and industry expansion during the pandemic boom through its 2023 report “COVID-19, the Surge in the Golf Industry, and the Post-Endemic Outlook” (Vol.5). In 2024, the report “Current Status and Future Challenges of the Golf Industry” (Vol.17) analyzed structural issues such as oversupply of golf courses, soaring fees, and regional demand disparities.

Building on these insights, this report turns to the more fundamental and long-term structural shifts facing the domestic golf industry. In particular, it explores how two major forces—demographic change and macroeconomic transformation—are expected to reshape golf demand over the mid to long term, and explores strategic pathways to address these shifts.

Domestic Golf Demand Declines for Two Consecutive Years—Has the Turning Point Arrived?

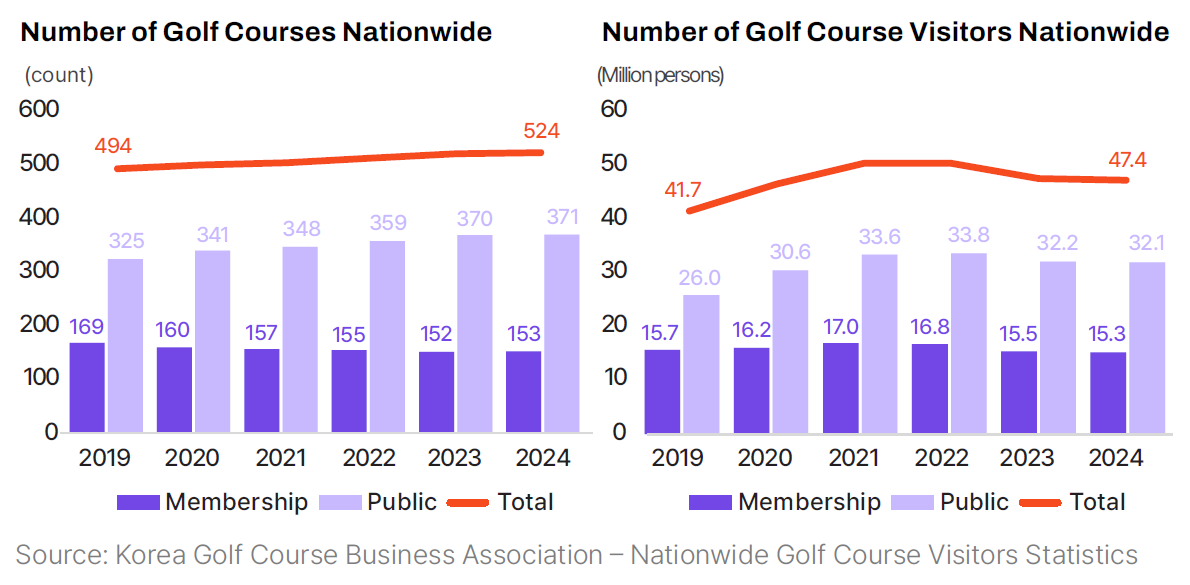

During the COVID-19 pandemic, South Korea’s golf industry benefited from social distancing policies and restrictions on indoor activities, which led to a surge in demand. However, following the transition to the endemic phase, the industry has entered a period of structural transition, marked by declining demand and continued expansion in golf course supply.

In fact, the total number of golf course visitors nationwide in 2024 reached approximately 47.4 million, down 0.6% from the previous year—marking the second consecutive year of decline. Over the same period, the number of golf courses increased from 522 to 524, further exacerbating the imbalance between supply and demand.

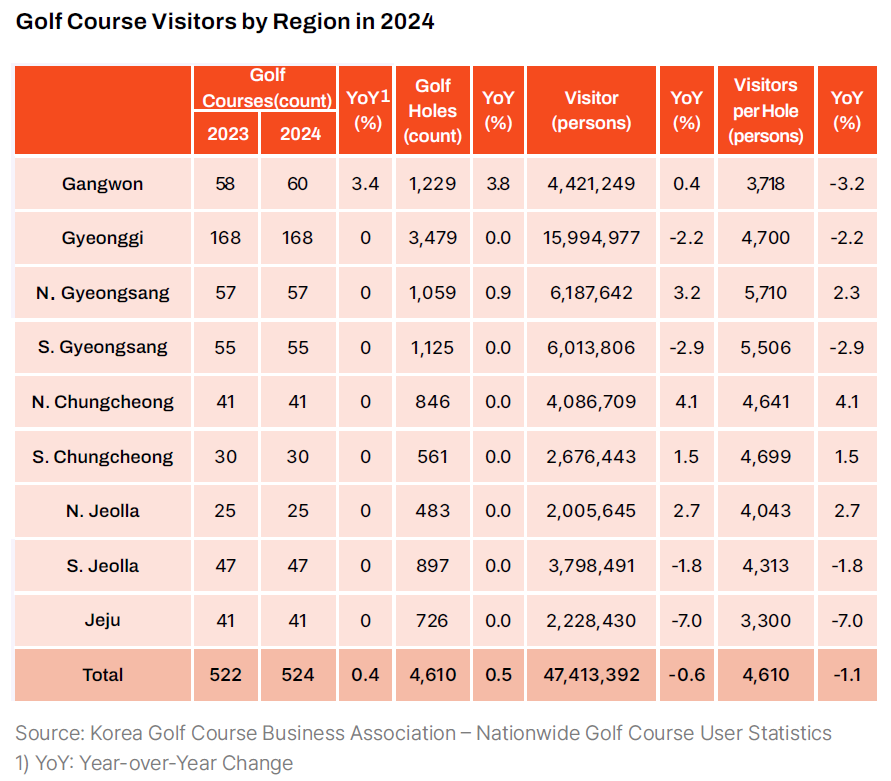

At the regional level, Jeju experienced the steepest decline, with golf course visitors dropping by 7% in 2024 compared to 2023. Other regions such as Gyeongnam, Gyeonggi, and Jeonnam also saw a contraction in demand. Notably, Gyeonggi Province—home to the largest number of golf courses and users—led the national decline, with a reduction of 360,000 visitors year-over-year.

In contrast, some regions including Gyeongbuk (+3.2%), Chungbuk (+4.1%), Chungnam (+1.5%), and Jeonbuk (+2.7%) recorded moderate increases in demand. However, the absolute scale of demand in these areas remained relatively limited and was insufficient to reverse the broader nationwide supply-demand imbalance.

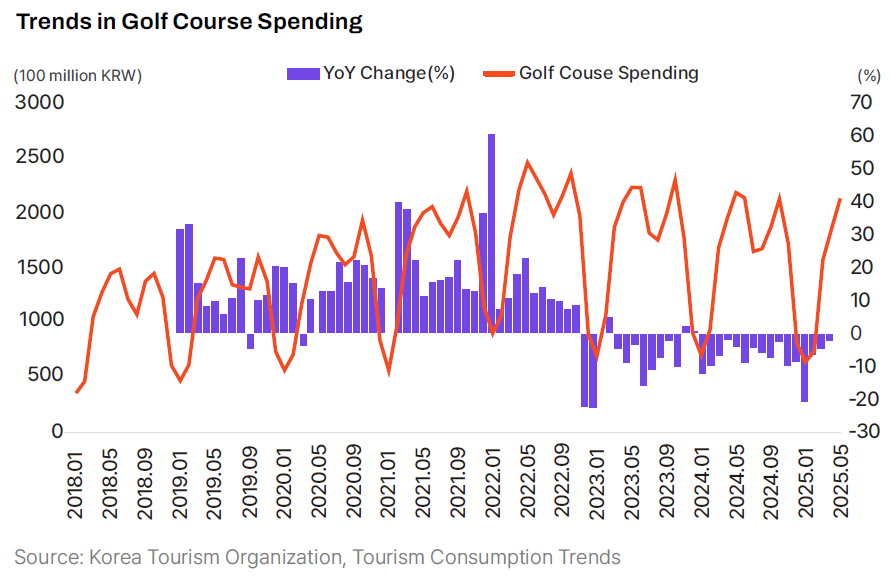

This downward trend is also reflected in spending data. According to the Korea Tourism Organization’s tourism expenditure statistics, domestic golf-related spending has declined for 16 consecutive months since the beginning of 2023, continuing through May 2025.

This suggests that the decline is not a short-term adjustment but may indicate a more structural contraction in demand. Rather than anticipating a simple rebound, the industry must now shift its focus to diagnosing the underlying causes of the decline and formulating mid- to long-term strategic responses.

Structural Decline in Golf Demand Driven by Demographic Shifts

The core reason behind the assessment that domestic golf demand is undergoing a structural, rather than temporary, decline lies in South Korea’s changing demographic landscape.

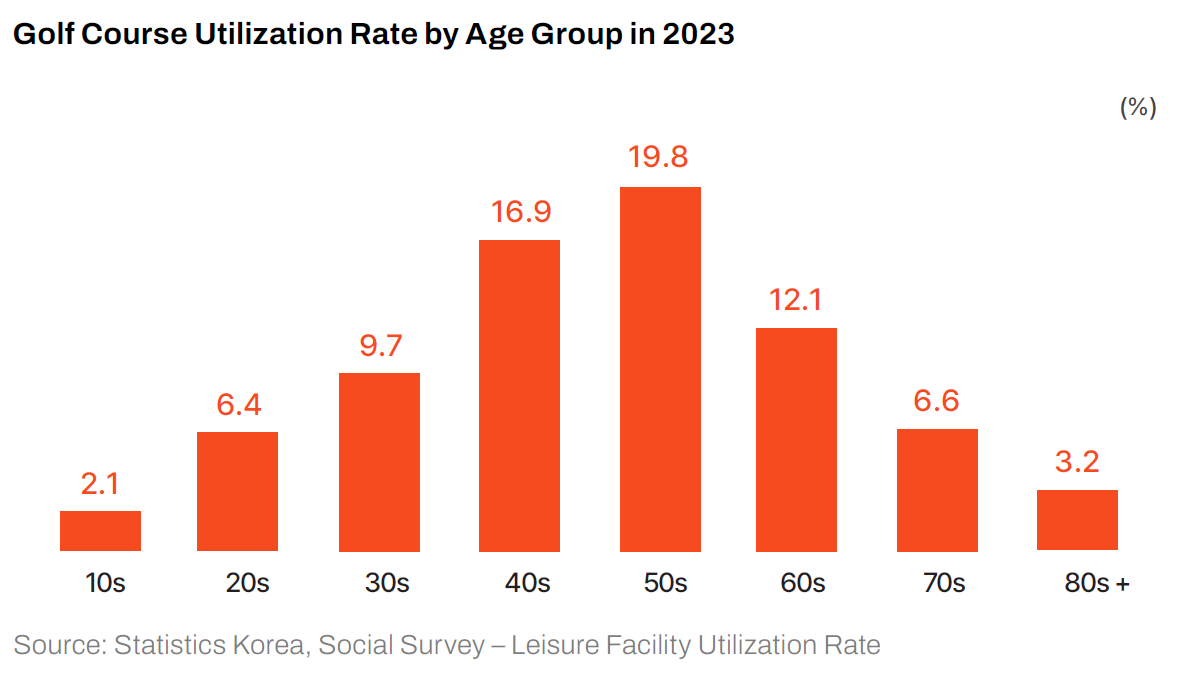

Currently, golf demand is heavily concentrated in specific age groups—particularly individuals in their 40s and 50s—while participation rates drop sharply among older cohorts. According to Statistics Korea’s 2023 Social Survey, the utilization rate of golf courses peaks at 19.8% among those in their 50s and remains high at 16.9% among those in their 40s. However, it drops to 12.1% in the 60s—a key retirement phase—and falls even further to 6.6% among those in their 70s and just 3.2% among those aged 80 and older. The data reveals a steep decline in golf participation as age increases.

This pattern is particularly concerning when viewed alongside the retirement of Korea’s baby boomer generation—the current core customer base for the domestic golf industry. The first wave of baby boomers (born 1955–1963, approx. 7.05 million people) and the second wave (born 1964–1974, approx. 9.54 million) together account for over 30% of the national population and have long formed the backbone of golf course clientele.

However, as this generation begins retiring in succession throughout the 2020s, their incomes decline and spending behaviors shift. Even those who previously held memberships or played frequently are now entering a phase where fixed income disappears and reliance on pensions or savings grows—making cost-intensive leisure activities like golf less financially viable.

This dynamic aligns with the age-based participation decline discussed above: even avid golfers in their 50s tend to drastically reduce their golf activity in their 60s and beyond due to economic and physical constraints.

2025: A Turning Point Toward Structural Decline in the Golf Population

Over the next decade, as the second wave of baby boomers reaches retirement age, downward pressure on golf demand is expected to intensify. Assuming age-specific golf participation rates remain constant, the size of the domestic golf population will inevitably decline due to demographic shifts alone.

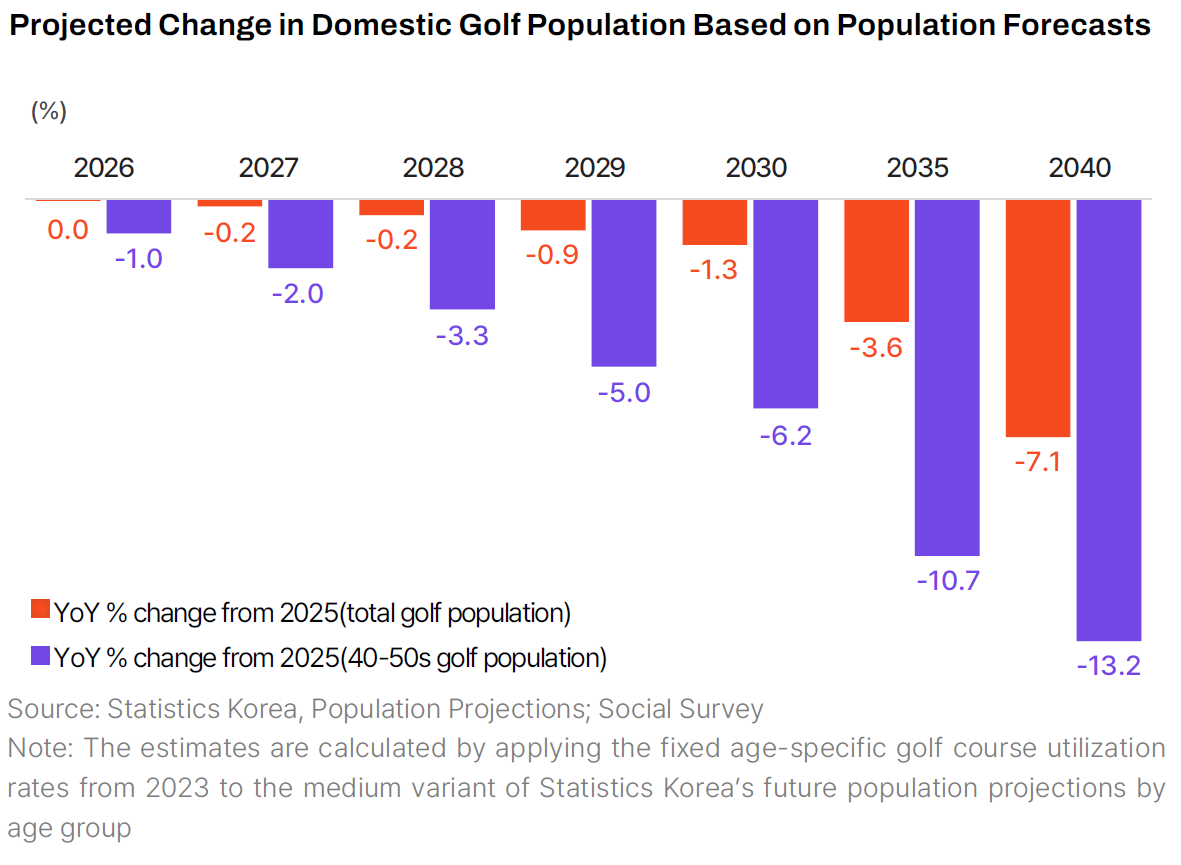

Projections based solely on population structure indicate that, by 2030, Korea’s total golf population will have decreased by 1.3% compared to 2025. More notably, the number of golfers in their 40s and 50s—the age group that currently accounts for the largest share of demand—is expected to fall by 6.2% during the same period.

This structural contraction is likely to be even more pronounced in non-metropolitan regions, where aging is progressing more rapidly than in the capital area. In these areas, population shrinkage is emerging as a fundamental threat to the sustainability of golf courses themselves.

Rather than a temporary adjustment, this trend may signal the beginning of a prolonged structural decline. If current age-based utilization rates hold, the number of golfers in their 40s and 50s is projected to drop by more than 10% by 2035—highlighting the urgency of long-term adaptation strategies.

Macroeconomic Outlook and Its Impact on the Golf Industry

In addition to demographic shifts, another critical variable threatening the foundation of golf demand is the broader macroeconomic environment.

South Korea is facing not only short-term economic deceleration but also a weakening of long-term growth momentum.

According to projections by the Korea Development Institute (KDI), Korea’s potential growth rate is estimated at 1.8% for the current year, and is expected to decline sharply to 1.5% during 2025–2030, 0.7% during 2031–2040, and just 0.1% during 2041–2050. In effect, Korea’s economic engine may come to a near halt within the next two decades.

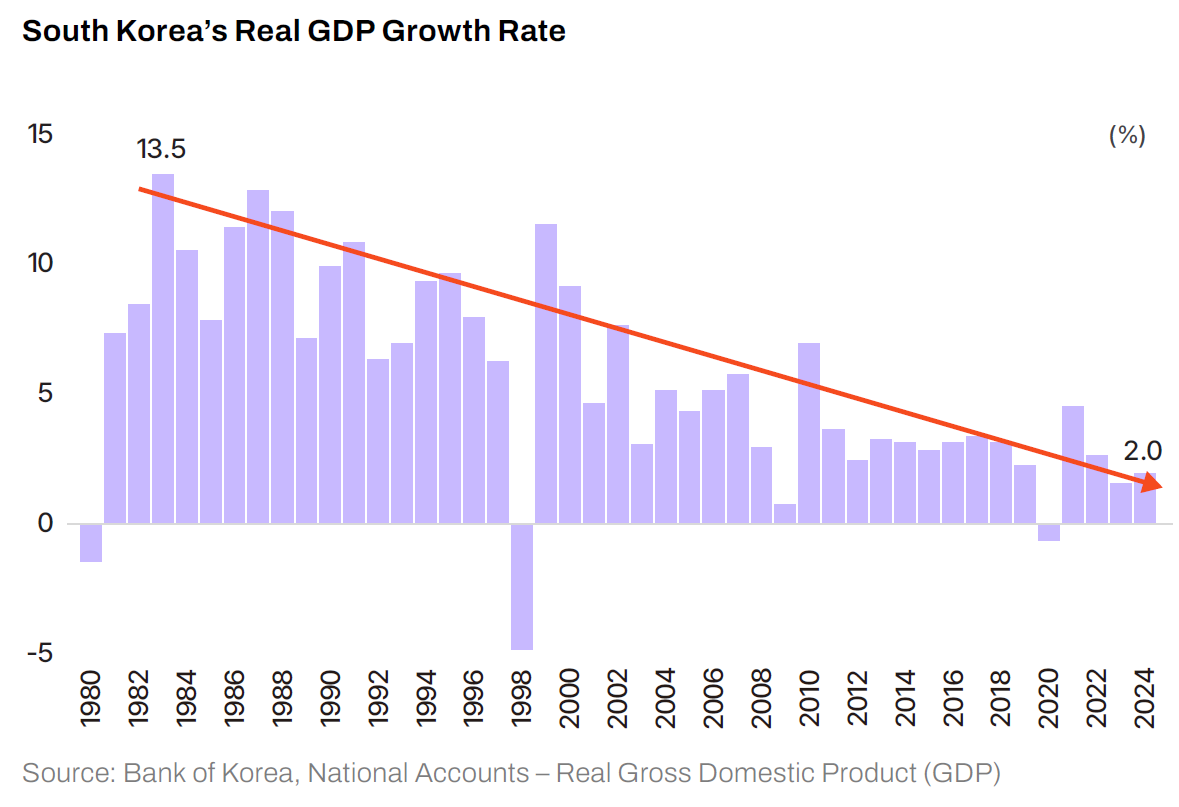

A similar trajectory is seen in real GDP growth. From a high of 13.5% in 1983, real growth has steadily slowed, reaching just 2.0% in 2024. In the first quarter of 2025, the economy contracted by –0.2%, marking a period of negative growth. Private consumption also declined by –0.1%, signaling continued weakness in domestic demand.

As Korea’s long-term growth potential continues to diminish and real growth trends downward, the golf industry—like other high-cost leisure sectors—is facing increasing structural headwinds. In periods of low growth, real disposable income rises more slowly, weakening purchasing power and prompting consumers to cut back on discretionary spending first. Golf, requiring both significant time and money, is often among the first activities to be scaled back during economic downturns.

Moreover, consumers in such times become more value-conscious, seeking alternatives that deliver greater satisfaction for the same cost. As a result, domestic golf courses now find themselves competing not only with other local leisure options but also with more cost-effective overseas golf destinations.

According to ConsumerInsight’s Weekly Travel Behavior and Plans Survey, the share of domestic golf travel has steadily declined—from 20.7% in 2021 to 16.0% in 2023—as overseas travel, long suppressed by the pandemic, resumed. Meanwhile, the proportion of those who played golf while traveling abroad for hobby or sport rose from 34.9% to 41.7% over the same period, suggesting that many Korean golfers are increasingly turning to Southeast Asian countries as attractive alternatives.

Cost is the dominant factor. A 2024 golf industry survey by Embrain found that 82.7% of respondents believe domestic green fees have become too expensive. Indeed, data from the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism show that the average weekend green fee at private membership golf courses in the Seoul metropolitan area reached KRW 290,000 in 2024. When caddie and cart fees are included, total per-person costs rise significantly higher.

In contrast, according to the Asia Golf Leaders Forum (AGL), the average spending per round in five Southeast Asian countries—Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Cambodia, and Indonesia—ranges between KRW 120,000 and KRW 180,000, roughly half the domestic level. Even after factoring in airfare, many golfers perceive overseas golf trips to be more economical.

Additionally, the appeal of combining golf with sightseeing abroad has amplified this shift, leading to a gradual outflow of spending by mid- to older-age golfers from the domestic market to international destinations.

Ultimately, the dual pressures of shrinking demand due to demographic aging and rising cost burdens amid economic stagnation are narrowing the foundation of domestic golf demand. In response, Korea’s high-cost golf industry must seek strategic approaches to alleviate price burdens and deliver greater value to increasingly selective consumers.

Structural Decline of Japan’s Golf Industry

Japan’s experience offers valuable insight, as the country has faced population decline, aging demographics, and prolonged economic stagnation earlier than Korea.

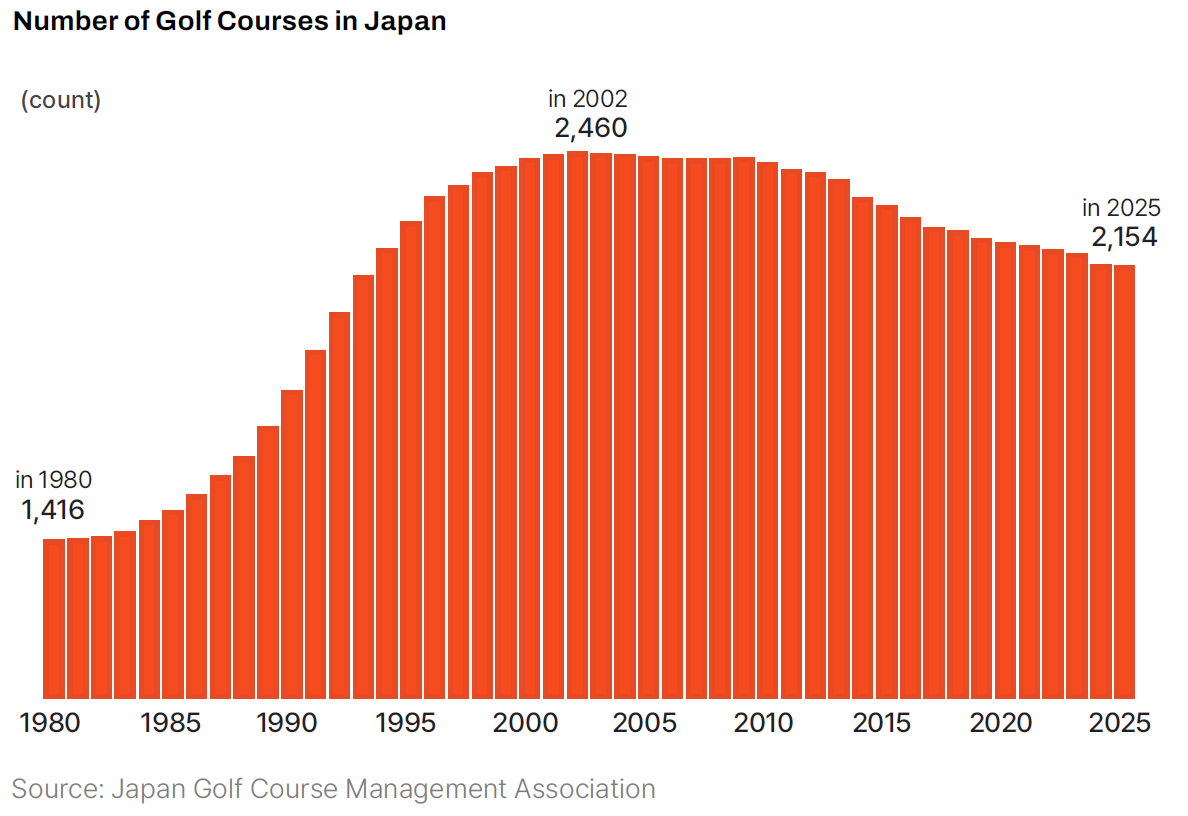

During the asset bubble of the 1980s, golf course development surged across Japan. According to the Japan Golf Course Business Association, the number of golf courses surpassed 2,000 by 1992 and peaked at 2,460 in 2002. However, as of April 2025, the total has declined to 2,154—marking a net reduction of 306 courses compared to the peak.

One of the primary drivers behind the decline in the number of golf courses has been the shrinking golf population. The retirement of Japan’s postwar generation—once the core of golf demand—combined with the burst of the asset bubble and prolonged economic stagnation, led to a steady erosion in participation.

According to the Korea Leisure Industry Institute, Japan’s golf population dropped from approximately 14.2 million in 1995 to 9.6 million in 2009, and further down to 5.6 million in 2021—just one-third of its peak level.

With demographic decline and weak economic growth becoming prolonged trends, Japan’s golf industry has clearly entered a post-peak phase of structural contraction.

Japan’s Golf Course Asset Prices Collapse to 10–20% of Korea’s Levels

Japan’s structural downturn in golf has extended beyond declining participation to a dramatic collapse in asset values surrounding the industry. During the early 1990s bubble era, golf memberships became speculative assets, with prices surging to unsustainable levels. According to the Nikkei Golf Membership Index, the index rose from 100 in 1982 to a peak of 948.17 in 1990. However, following the burst of the bubble, it plummeted to 57.79 by 2002—just one-sixteenth of its peak value.

For instance, a membership at Koganei Country Club, a prestigious course near Tokyo, which exceeded JPY 400 million in the early 1990s, dropped to around JPY 40 million in the 2000s and, as of 2025, trades at roughly JPY 60 million (per AAA Golf Web), representing just 15% of its peak value.

Golf course transaction prices followed a similar trajectory. During the bubble period, construction costs for 18-hole courses often exceeded JPY 20 billion, but by the 2010s, smaller regional courses were frequently auctioned off at a fraction of that. For example, Kushiro Crane Country Club in Hokkaido—an 18-hole course with a three-story clubhouse—was listed at a minimum auction price of just JPY 31.28 million, while Kanna Golf Club in Gunma sold for only JPY 38.55 million in 2009, recovering just a sliver of the original land and facility investment.

According to Golf Course Corporate Groups & Affiliations published by Ikki Publishing, the average transaction price for an 18-hole golf course in Japan was JPY 810 million in 2022—equivalent to JPY 50 million per hole (approximately KRW 500 million). Even courses near Tokyo are not exempt from this trend. Yamamoto Property Advisory, a Japanese real estate consulting firm, estimated that in 2024, per-hole prices around the Tokyo area averaged JPY 100 million (KRW 1 billion).

This is less than 20% of the per-hole prices seen in Korea’s capital region—for example, KRW 8 billion at Montvert CC (Pocheon, 2023) and KRW 7 billion at Serazio CC (Yeoju, 2024).

The more fundamental concern is that this prolonged decline may not simply be a cyclical correction. Around 2025, Japan’s Dankai generation (born 1947–1949), who began golfing during the bubble era, will be entering the 75+ super-aged bracket, accelerating the erosion of the golf demand base.

Having already become a super-aged society in 2006—two decades ahead of Korea—Japan’s golf industry is now structurally constrained by demographic shifts, making a long-term recovery unlikely regardless of economic conditions.

Japan’s Strategic Responses Amid Structural Decline in Golf

In the face of prolonged structural contraction, Japan’s golf industry has pursued a range of survival strategies.

First, many golf courses have shifted their business models. Following the collapse of the asset bubble, a significant number of golf courses were acquired by foreign investment funds and pivoted away from membership-based operations toward mass-market, low-cost models. Today, a large share of Japanese courses operate without caddies and utilize dynamic pricing schemes that adjust based on demand. Some weekday morning packages even offer 18-hole green fees including breakfast for as little as JPY 10,000 (approx. KRW 100,000). These approaches aim to reduce labor costs, improve operational efficiency, and lower price barriers to stimulate demand.

Second, efforts have been made to attract overseas demand. In response to declining domestic participation, local governments and golf courses have begun collaborating to draw foreign golfers by lowering prices and offering incentives. For instance, Ibaraki Prefecture operated charter flights between Ibaraki Airport and Korea’s Cheongju Airport three times a week, and in the winter of 2024, launched a campaign providing Korean golfers with up to JPY 25,000 per person in lodging subsidies. These golf-tourism-linked promotions are emerging as a key survival strategy for regional courses, supported by aggressive marketing and incentives from local authorities.

Third, the industry is working to cultivate new demand. With the long-term decline in golf participation, Japan has come to recognize—albeit belatedly—the importance of attracting women and younger generations. A variety of campaigns are now underway, including junior golf development programs, beginner tee-up events, and festivals that combine golf with fashion and entertainment. These efforts to introduce golf to people in their 20s and 30s and nurture them into long-term customers offer meaningful implications for Korea as well.

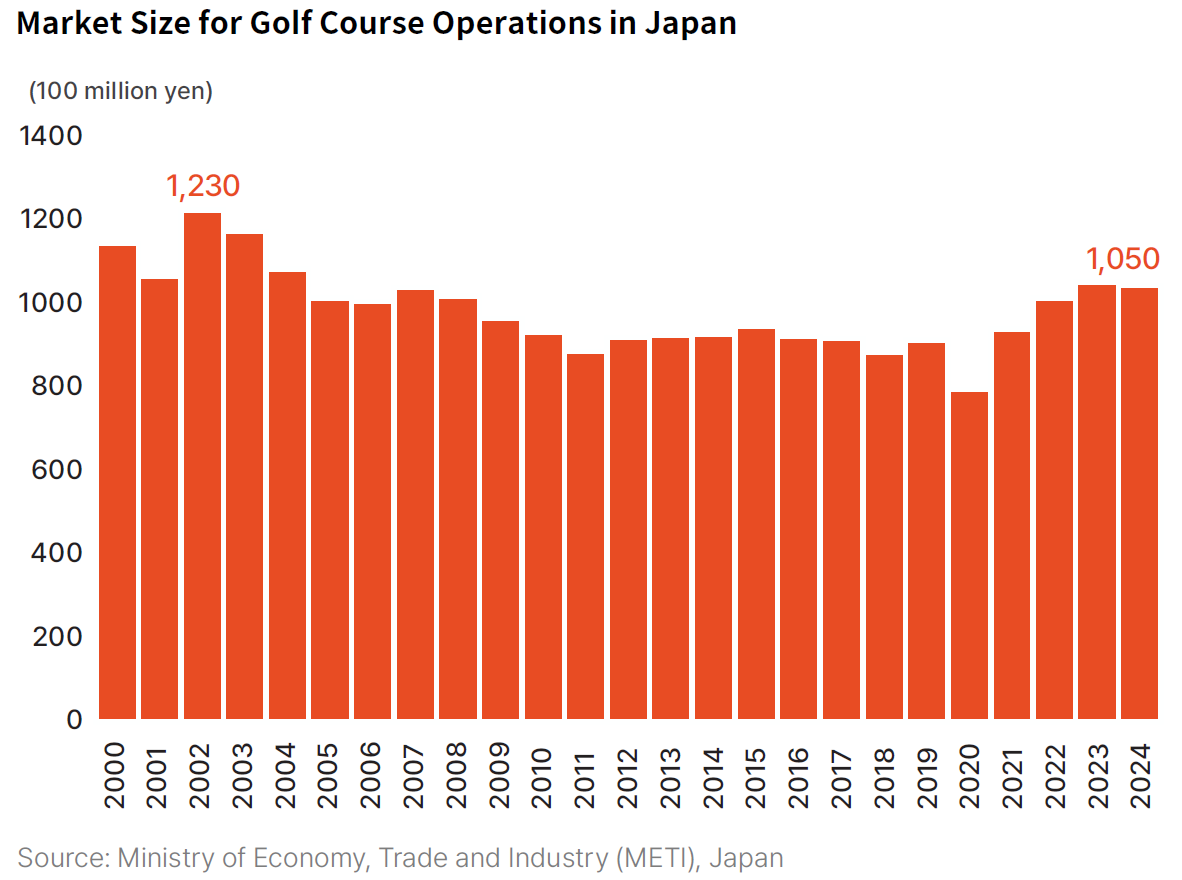

Despite these efforts, however, the size of Japan’s golf course market has shown little improvement. According to data from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, the total market size of golf course operations stood at JPY 105 billion in 2024, down from JPY 123 billion in 2002—reflecting a decline over the past two decades.

Japan’s experience offers a clear warning: without proactive adaptation to demographic shifts, industries inevitably face shocks from oversupply and shrinking demand. At the same time, the case demonstrates that strategies such as pricing innovation, service diversification, and linkage with overseas markets can serve as partial buffers in times of industry crisis.

Korea can no longer afford to view Japan’s path as a distant scenario. Given the structural similarities in demographics and macroeconomic trends, the Korean golf industry is highly susceptible to following a similar trajectory.

What is needed now is not short-term demand stimulation, but a forward-looking response that restructures the industry and secures a sustainable demand base in line with demographic realities. This requires more than just recognizing the threat—it calls for faster and more sophisticated actions than Japan, including systematic supply adjustments, diversified revenue models, and targeted cultivation of external demand.

Korea’s Shrinking Golf Demand Base: Rethinking Industry Outlook and Strategic Response

Korean society is undergoing a fundamental transformation, marked by low birth rates, rapid aging, and decelerating economic growth. The retirement of the baby boomer generation—once the core of golf demand—is accelerating, while real GDP growth continues to slow and private consumption weakens. Against this backdrop, golf, as a high-cost leisure activity, is gradually being deprioritized in consumer spending.

The pandemic-driven boom has ended, and the post-endemic decline in both users and spending is emerging as a clear signal of structural contraction rather than a temporary correction. As of 2024, golf course users in Korea have declined for two consecutive years, and golf-related credit card expenditures have fallen for 16 straight months. These trends underscore the urgency of shifting industry strategy away from simply stimulating demand toward acknowledging and adapting to a fundamental contraction of the demand base.

A structural response must be built on three key pillars:

First, the introduction of full-scale Revenue Management systems that enable flexible, demand-sensitive pricing. Most Korean golf courses still adhere to rigid, fixed pricing models. Yet, given that tee times are a perishable inventory, dynamic pricing based on demand forecasting is critical. Rancho Park Golf Course in Los Angeles, for example, segments rates by weekday, weekend, and time of day—offering “Super Twilight” discounts for low-demand slots to maximize yield.

In Korea, signs of change are emerging. According to Embrain’s 2023 survey, 82.3% of adult golfers expressed interest in no-caddie (self-rounding) play, and some public courses have introduced unmanned check-in and self-cart systems to reduce operating costs while improving accessibility. These efficiency and pricing strategies are not just about lowering costs—they aim to deliver greater value through targeted price-service alignment based on time slot, customer segment, and demand level.

Second, it is critical to build new demand beyond domestic limits by cultivating inbound golf tourism and integrated golf-tourism packages. Ibaraki Prefecture in Japan, for example, runs regular charter flights from Korea’s Cheongju Airport and offers incentive campaigns targeting Korean golfers. Major Southeast Asian golf resorts bundle accommodations, golf, massage, and sightseeing at highly competitive prices—making destinations like Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia increasingly attractive to Korean golfers based on value-for-money. Korean golf courses must innovate their offerings to match or exceed this international competition in both pricing and content.

Third, structural adjustments to oversupply and functional repurposing of golf course assets must be pursued. While demand is shrinking, the number of golf courses in Korea continues to rise—widening the mismatch between supply and demand. If left unaddressed, this imbalance could lead to deteriorating profitability, price collapses, and intensified operational risk across the industry.

Selective restructuring of underperforming golf courses is required, alongside strategies to convert these assets into community-oriented spaces. Japan has already seen diverse redevelopment examples. In 2017, a closed golf course in Hyogo Prefecture was repurposed into a mega solar power plant supplying electricity to 29,000 households annually—effectively utilizing the site’s scale and infrastructure for environmental benefit.

Other conversions across Japan include transforming abandoned golf courses into parks, housing complexes, and rural experience villages. These are not mere demolitions or asset liquidations, but long-term strategies designed to enhance community integration and sustainability.

By shifting golf course land into public parks, rural retreats, solar farms, or residential areas, the industry can move beyond short-term profitability to contribute meaningfully to regional revitalization. Rather than indiscriminate expansion, strategic downsizing and asset repurposing aligned with demand realities can serve as guiding principles for Korea’s future golf policy.

Conclusion

The current challenges facing Korea’s golf industry may not merely reflect a cyclical downturn. Rather, they signal the structural impact of two powerful gravitational forces—demographic change and macroeconomic transformation—simultaneously eroding the foundation of demand. The time has come to shift from efforts to sustain the pandemic-driven surge through artificial demand stimulation to a fundamental restructuring of the industry that aligns with the new demand landscape.

To be clear, the recent decline in demand is not solely the result of structural shifts. The dissipation of COVID-induced demand, broader economic slowdown, outbound demand leakage, and reduced corporate spending have also contributed as short-term factors. However, these adjustments may in fact be early signs of a deeper structural decline—one that is likely to accelerate over the next decade as the retirement of the baby boomer generation progresses in full.

This underscores the urgency for all stakeholders—including government agencies, golf course operators, and related industries—to begin preparing long-term strategic responses now, before the industry enters a more pronounced phase of demand contraction.