Deachul (David) Seo / Senior Researcher, Yanolja Research / [email protected]

Kyuwan Choi / Professor, Kyung Hee University & Director, H&T Analytics Center / [email protected]

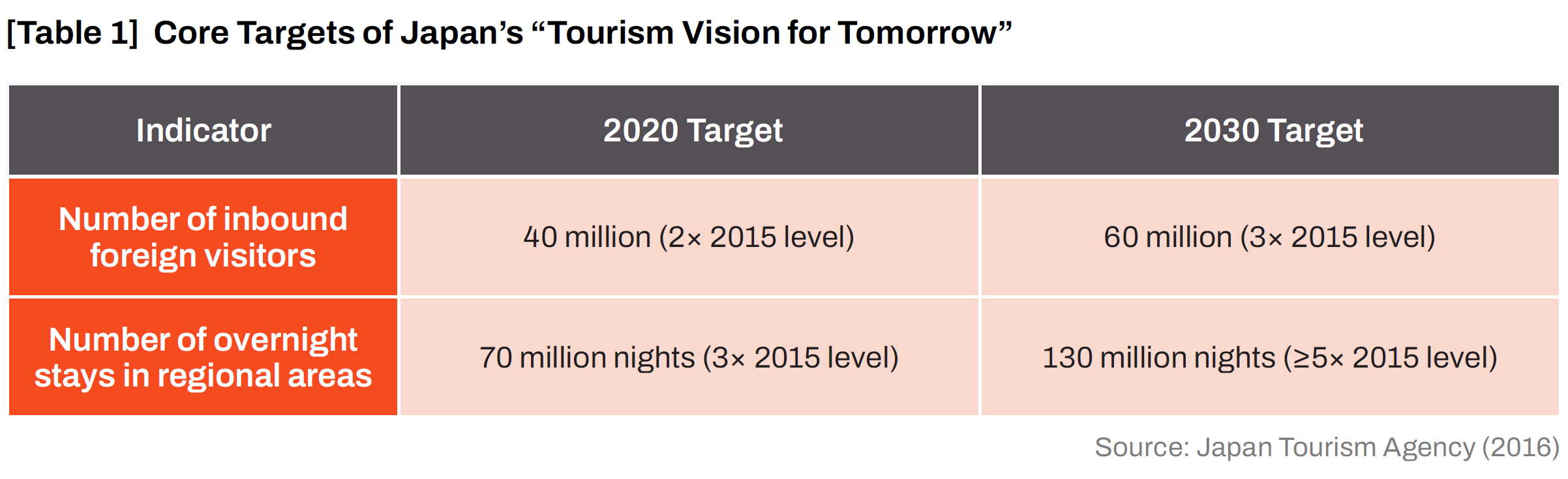

In March 2016, the Japanese Cabinet adopted the 「Tourism Vision to Support the Future of Japan(明日の日本を支える観光ビジョン)」 as a mid- to long-term national strategy. Tourism was positioned not merely as a consumption sector, but as a structural engine for countering regional economic decline driven by demographic contraction. A central objective of the vision was to attract and disperse inbound tourism demand into regional areas.

To this end, policy attention focused not only on increasing inbound arrivals, but on expanding regional overnight stays, explicitly addressing the overconcentration of tourism in major metropolitan hubs. However, Japan’s aviation structure at the time stood in stark contrast to this goal. As of 2015, only about 5.4% of inbound visitors entered through regional airports, with the vast majority concentrated at Narita, Haneda, and Kansai.

This mismatch led policymakers to identify the international air network itself as a structural bottleneck to regional tourism dispersion, reframing airport access as a core tourism policy issue rather than a neutral transportation matter.

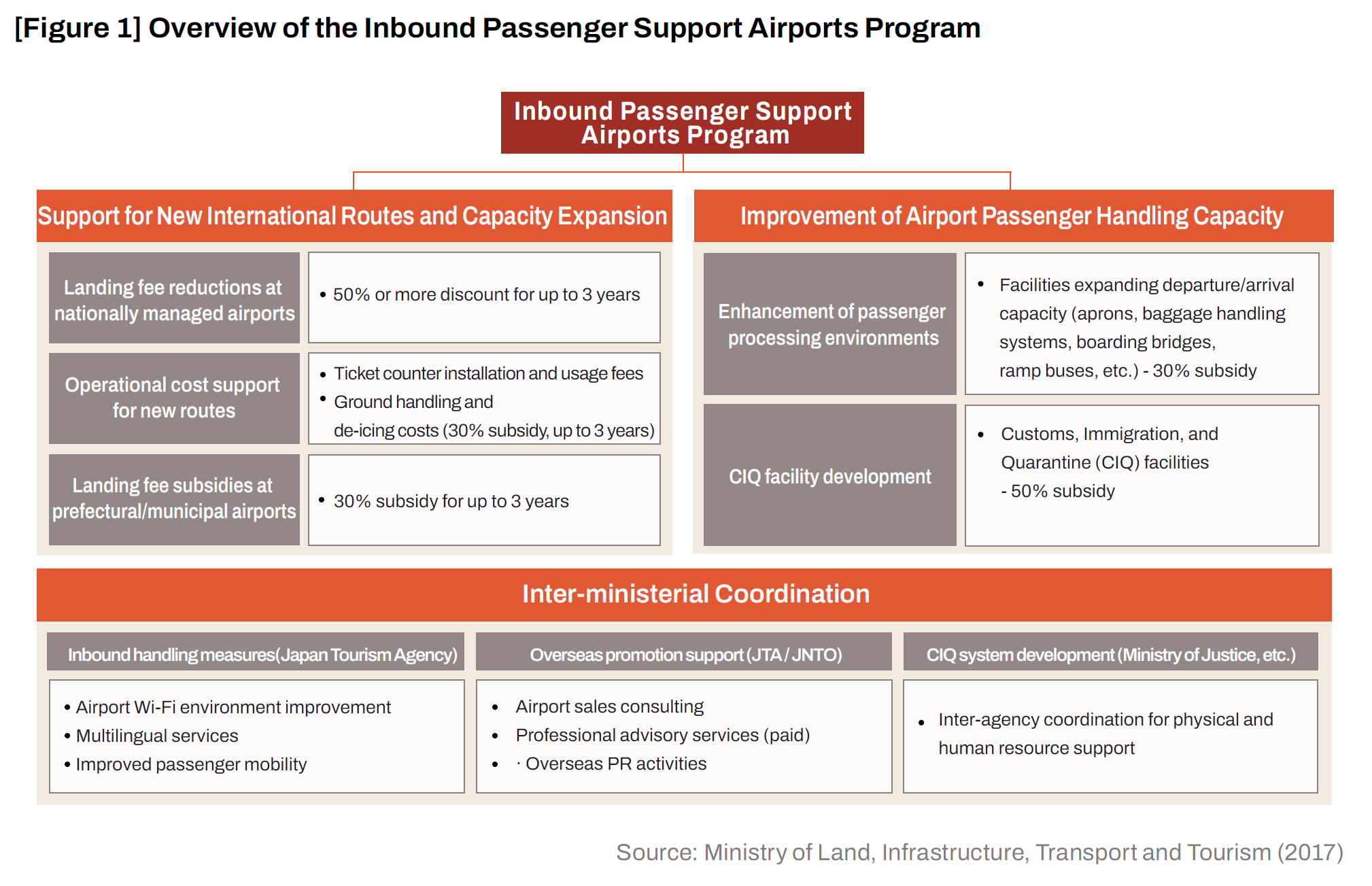

In response, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) launched the Inbound Passenger Support Airport Program in 2017. The program redefined regional airports as strategic gateways for inbound tourism, aiming to stimulate regional economies by promoting international air services—particularly those operated by foreign carriers—at non-hub airports.

The program rests on three pillars:

Financial support was provided through temporary reductions or subsidies on international landing fees and partial coverage of early-stage operating costs, including ground handling and de-icing. In parallel, investments were made to upgrade terminal facilities and CIQ capacity to ensure that airports could practically absorb increased inbound demand. These measures were complemented by overseas promotion, multilingual services, and regulatory coordination led by the Japan Tourism Agency (JTA) and the Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO).

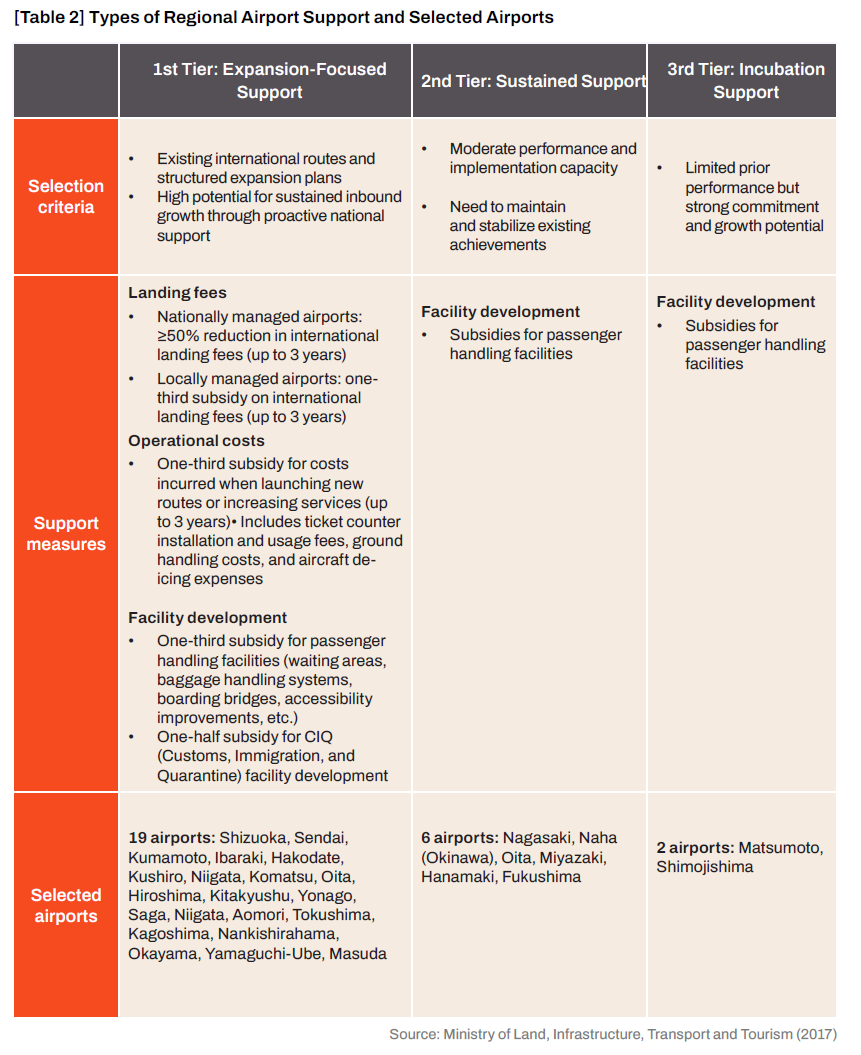

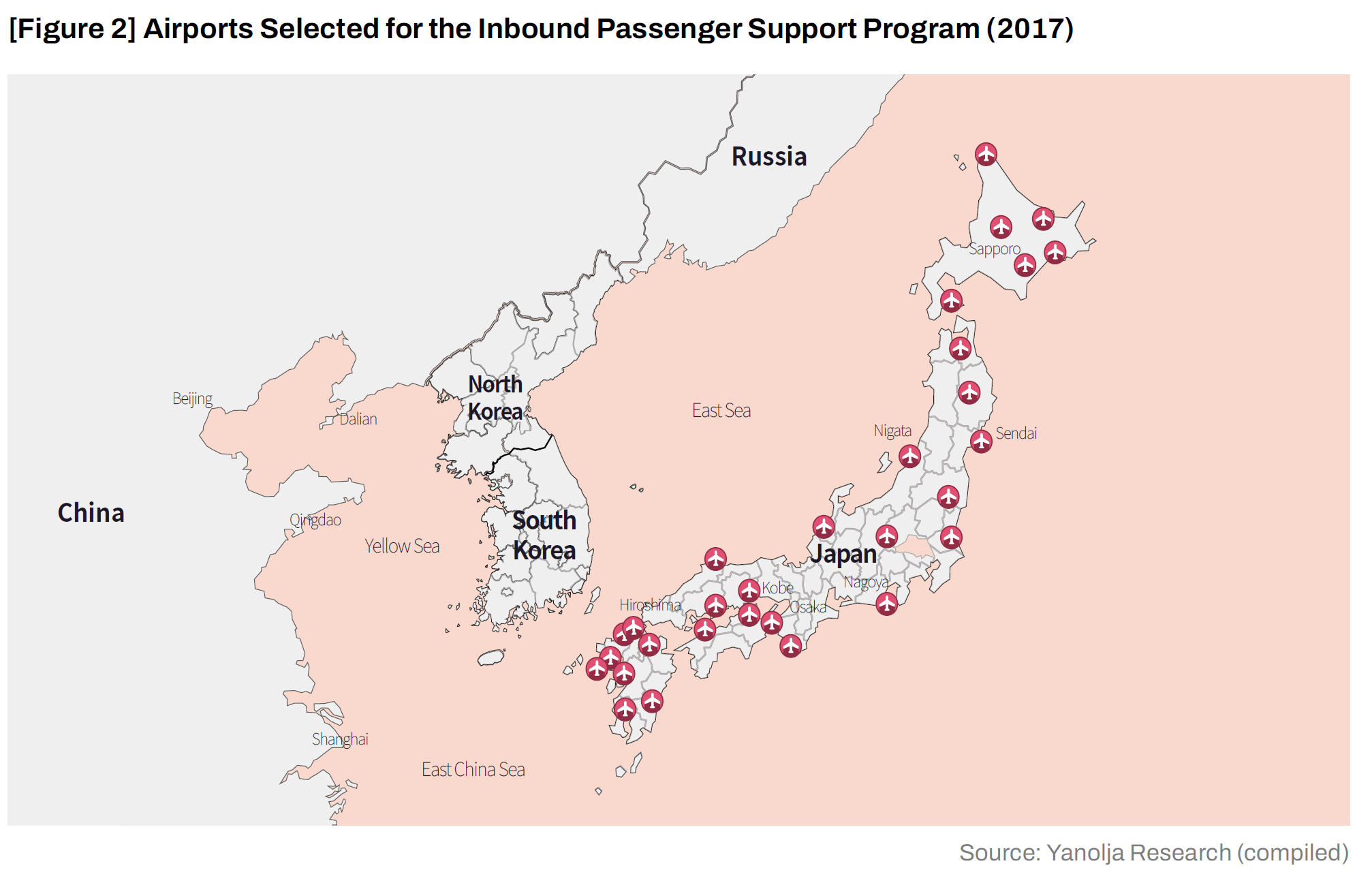

In its first year, the program designated 27 regional airports (excluding major hubs) and classified them into three tiers—Expansion, Sustained, and Development Support—based on existing performance and growth potential. This tiered approach institutionalized a logic of selection and concentration, enabling limited fiscal resources to be allocated strategically toward airports with higher expected returns.¹

¹ Based on the Civil Aviation Bureau’s FY2019 budget proposal and related explanatory materials, the annual budget allocated to the Inbound Passenger Support Airport Program is estimated at approximately JPY 0.8–1.0 billion.

2 Within Hokkaido, six airports—operated under a private concession by Hokkaido Airports Co., Ltd.—are collectively counted as a single airport for the purposes of this program.

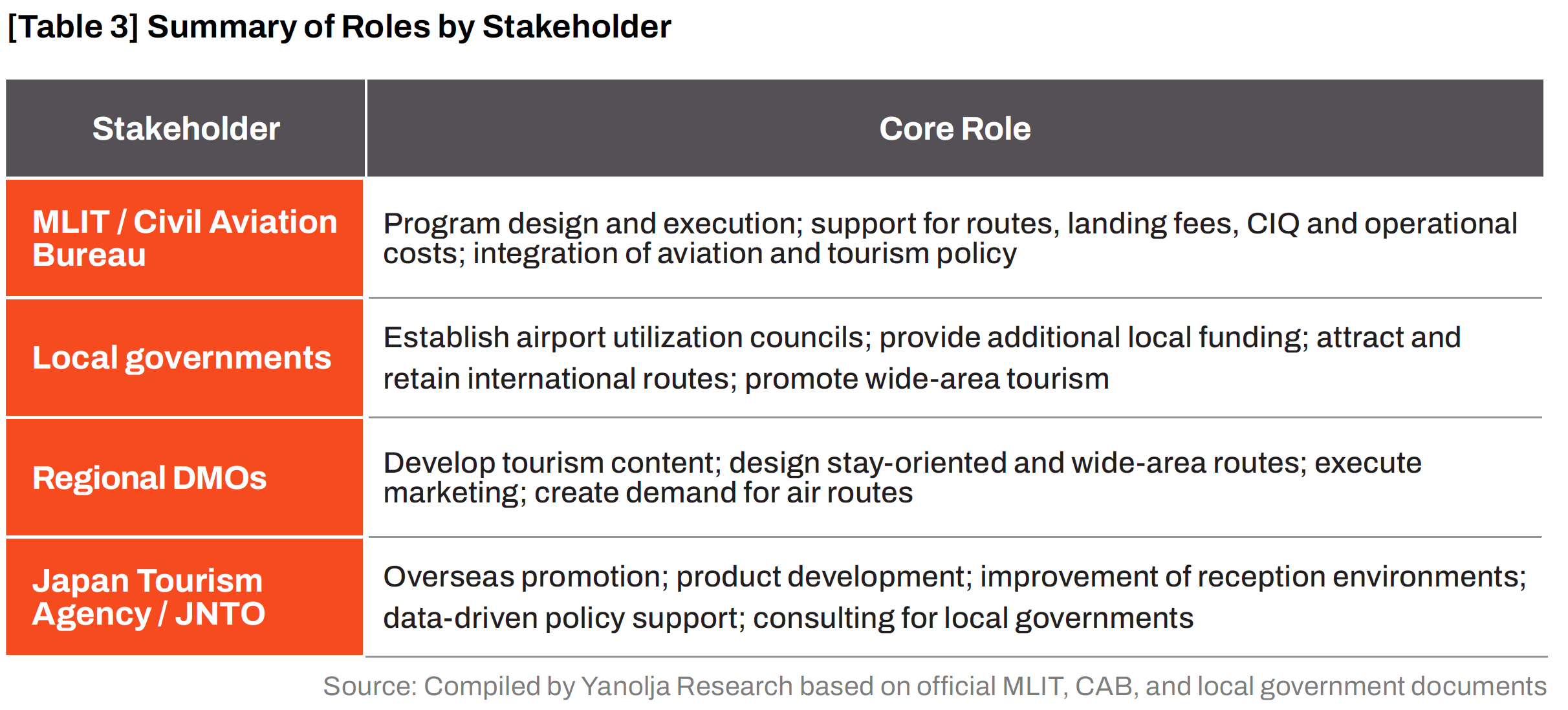

The program operated within a multi-layered governance structure involving MLIT, the Civil Aviation Bureau (JCAB), local governments, and regional DMOs (Destination Management Organizations). MLIT and JCAB functioned as a single policy unit, combining institutional design with operational execution through route licensing, fee reductions, and CIQ support.

Local governments served as primary implementing actors, forming airport utilization councils and deploying additional fiscal resources to support route sustainability. In several regions, municipalities collaborated beyond individual airports to pursue wide-area tourism strategies.

Regional DMOs played a pivotal role in linking air services to actual tourism demand by designing stay-oriented routes, packaging content, and executing targeted marketing. JTA and JNTO provided complementary support through overseas promotion, visitor readiness improvements, and data-driven policy assistance.

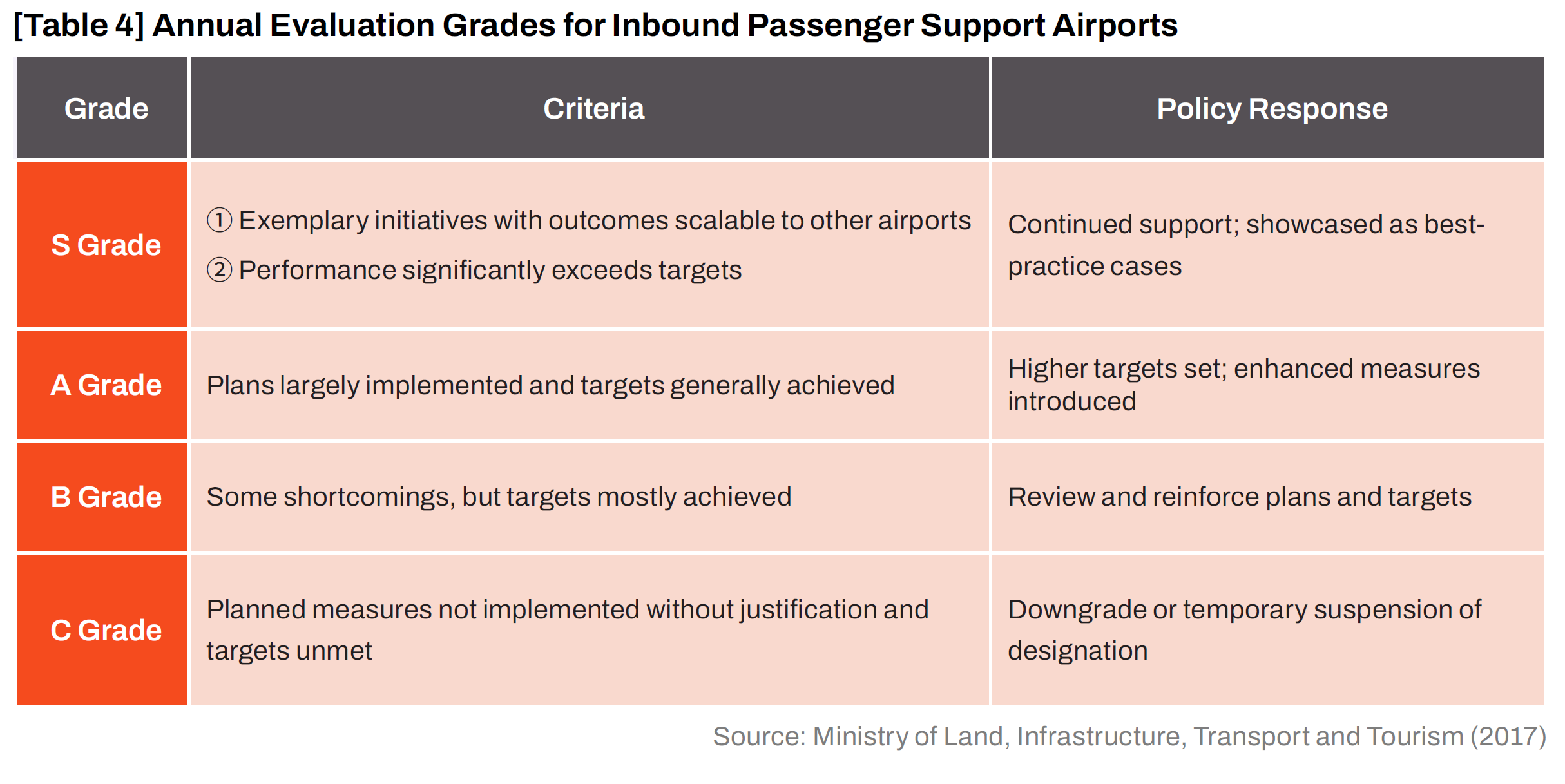

Program performance was assessed annually by an external expert committee using predefined quantitative indicators (i.e., KPIs)—such as inbound passenger numbers and scheduled international services—alongside qualitative criteria related to inbound readiness and sustainability.

Airports were graded on a four-tier scale (S/A/B/C). Importantly, the highest grade (S) required not only strong numerical outcomes but also demonstrable, replicable practices linking air connectivity to regional tourism consumption. This framework shifted evaluation away from headline growth alone toward the quality of strategies and execution mechanisms.

A notable feature of Japan’s evaluation framework is that it incorporated qualitative criteria related to the sustainability of inbound readiness at both the airport and regional levels, alongside quantitative outcomes. For example, Expansion Support airports were required to meet baseline conditions such as improvements to Wi-Fi infrastructure, enhancements to secondary ground transportation for airport access, and the creation of hospitality spaces within terminals. In addition, evaluators assessed a range of qualitative factors through review comments, including the extent of inter-municipal cooperation, the stability of ground-handling operations, the sophistication of market analysis by target country and traveler segment (e.g., FIT travelers), and preparedness systems for responding to emergencies or disasters.

Accordingly, the evaluation of the Inbound Passenger Support Airport Program was structured to go beyond the question of how many passengers increased. It explicitly examined the strategies and execution mechanisms that enabled those outcomes. In particular, airports receiving an S grade were not simply those with strong headline results, but those that demonstrated how local governments, from a tourism perspective, effectively linked air service supply to regional stays and visitor spending. This evaluation structure is reflected clearly in the exemplary cases which are discussed in the following section.

While the Inbound Passenger Support Airport Program provided a common starting point for regional airports, outcomes diverged markedly thereafter depending on how each region interpreted its own conditions and translated them into context-specific solutions. Some airports went beyond treating national support merely as a means of cost reduction, instead combining it with tailored responses that reflected local constraints and opportunities. Through this process, they differentiated themselves in how outcomes were generated rather than simply how much support was received. These differences were clearly reflected in the results of the annual evaluations.

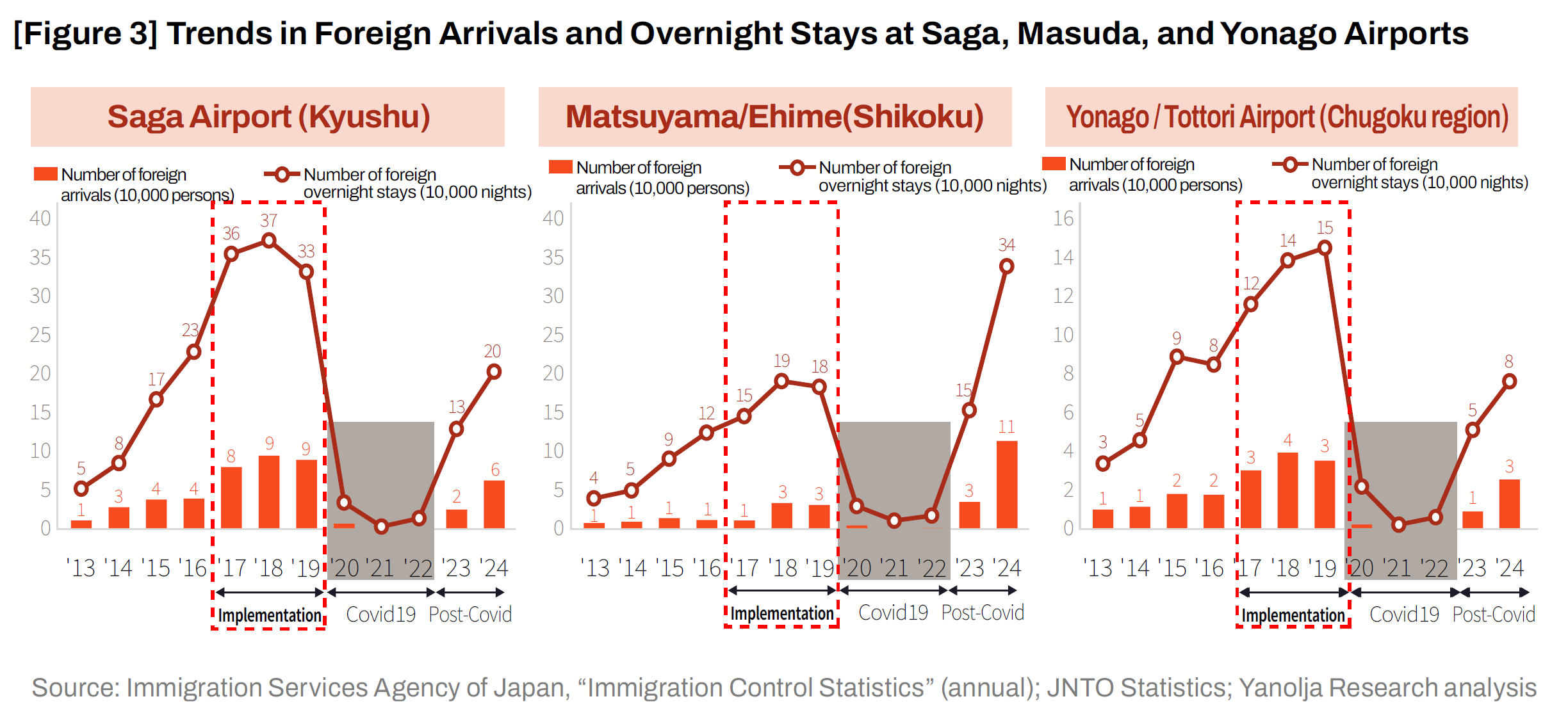

In the program’s second year, 2018, several regional airports—including Saga, Matsuyama, Yonago, and Kumamoto—received S-grade evaluations. What these airports shared was a common approach: they began by identifying the region’s inherent physical or market constraints and then either proactively removed key bottlenecks or constructed collaborative frameworks at the regional level. As a result, they were recognized as best-practice cases with lessons applicable to other airports. Selected examples are outlined below.

Saga Airport in the Kyushu region identified poor accessibility and limited post-arrival mobility as its primary structural challenge. To address this demand-side bottleneck, the local government introduced a direct bus service linking downtown Fukuoka with Saga Airport, alongside a low-cost rental car program within the airport (JPY 1,000 per day). This intervention focused on improving the visitor experience after arrival, rather than on route attraction alone. Within two years of the program’s launch, the number of inbound passengers arriving via routes from China and Thailand approximately doubled.

Matsuyama Airport in the Shikoku region (Ehime Prefecture) adopted a strategy that explicitly acknowledged the area’s limited domestic catchment demand. Rather than relying on domestic traffic, the local government combined foreign carrier attraction with proactive tourism demand creation. Agreements were concluded with low-cost carriers (LCCs) from neighboring Asian markets, under which the local government agreed to compensate losses if seat occupancy fell below a predefined threshold (70%) for a limited period. In parallel, the regional DMO worked with airlines to develop travel products and conduct on-site marketing. As a result, actual load factors reached 85%, allowing routes to stabilize without triggering compensation payments.

A particularly notable outcome is the sharp increase in foreign overnight stays in Matsuyama. As of 2024, the number of foreign guest nights had increased by nearly 200% compared to pre-pandemic levels in 2019. During this period, a new Busan–Matsuyama route was launched, and overnight stays by Korean visitors grew by approximately 300%. These outcomes reflect the cumulative effect of pre-pandemic efforts to build an inbound-oriented aviation and tourism supply base centered on the airport, which aligned closely with the post-pandemic expansion of demand for small-city travel. In other words, post-crisis performance did not emerge by chance, but materialized on top of aviation and tourism structures that had been deliberately established prior to the crisis.

Yonago Airport in the Chugoku region (Tottori Prefecture) likewise recognized the difficulty of sustaining international demand through a single airport alone. In response, it formed the San’in Tourism Area[3] consortium in collaboration with the neighboring Izumo region. By treating Yonago and Izumo airports as a single tourism gateway and developing open-jaw routes—allowing travelers to arrive through one airport and depart through the other—the region increased load factors on routes to Taiwan and Hong Kong to over 80%. Consequently, the annual number of inbound visitors rose from approximately 18,000 prior to the program to 39,000 in 2018, more than doubling within a short period.

What these cases collectively demonstrate is that national support—through landing-fee reductions and subsidies for operating and facility costs—served only as a starting point for revitalizing regional airports. The Inbound Passenger Support Airport Program mitigated the structural cost burdens associated with launching international services and thereby created the conditions under which route entry could be attempted. However, it did not constitute a framework in which the national government guaranteed route sustainability or the expansion of tourism outcomes.

Airports that succeeded in sustaining and expanding performance distinguished themselves by what followed after the initial phase of national support. In these cases, local governments took the initiative in creating demand, complemented by regional collaboration, additional local fiscal investment, and close coordination with DMOs. Rather than relying solely on central government assistance, they actively shaped the mechanisms through which air services were translated into tourism activity and economic outcomes.

In this sense, the Inbound Passenger Support Airport Program is best understood not as a policy that offered a definitive solution to regional airport revitalization, but as a policy starting line—a foundational framework that opened the conditions under which multiple stakeholders could collaborate to generate tangible results. It functioned less as a ready-made answer and more as a structural foundation upon which locally driven strategies and execution could take hold.

Japan’s experience with the Inbound Passenger Support Airport Program demonstrates that regional airports can be effectively positioned as gateways for inbound tourism. At the same time, there are clear limitations to directly transplanting this model into the Korean context. Rather than replicating Japan’s approach wholesale, careful consideration is required to adapt policy directions to Korea’s specific aviation and tourism structures.

First, Korea must rebalance its outbound-oriented air supply by strategically expanding inbound-oriented services operated by foreign carriers. Slot-based incentives at selected regional airports may be more effective than generalized route subsidies.

Second, inbound conversion depends less on hinterland size than on local governments’ capacity to create demand through targeted marketing, stay-oriented products, and inter-regional collaboration.

Third, sustainable outcomes require clearly defined roles and shared accountability among the central government, airport operators, and local governments, supported by matching-fund budget structures and close DMO coordination.

For this governance structure to function effectively, each stakeholder must act with a clear understanding of its role:

Fourth, addressing the “broken journey” between Incheon and regional airports is critical. Aligning route strategies and transfer systems across airport authorities could allow metropolitan inbound demand to flow more organically into regional destinations.

Finally, air services merely open the door; sustained demand depends on post-arrival experience design. Local mobility, coherent travel routes, and continuous promotion are essential for converting arrivals into regional economic impact.

Japan’s Inbound Passenger Support Airport Program demonstrates that regional airport revitalization begins not with infrastructure alone, but with governance structures that enable local initiative. National support lowered entry barriers, but durable outcomes emerged where local governments actively shaped demand through collaboration, investment, and execution.

The key lesson is clear: opening an airport is not the end point, but the starting line. When policy objectives, budget structures, stakeholder roles, and visitor experience design are aligned, regional airports can function as powerful levers for transforming inbound tourism structures. For Korea, repositioning regional airports from peripheral infrastructure to strategic tourism gateways represents a critical step toward rebalancing inbound growth and regional development.